Jamestown Rediscovery was happy to welcome eleven students to this year’s archaeological field school, where the archaeology and collections teams taught a hands-on archaeology primer from late May through early July. The students learned a broad range of archaeological, conservational, and curatorial techniques that will serve as a solid foundation should they pursue a career in archaeology/collections or a related field. The students excavated hand-in-hand with our archaeologists at several sites at Jamestown and similarly were taught and guided through their collections work by our conservators and curators in the lab and Vault.

Most of the excavations were conducted in Smithfield, an area largely unexplored by archaeologists but which is now approached with a sense of urgency because it is flooding with increasing regularity. Saturated soil makes archaeology much more difficult because the transition from an aerobic to anaerobic environment changes the color of the soil, making features blend in with the soil surrounding them. The constant wet/dry cycles that Smithfield is experiencing are also harmful to human remains, turning bones soft and then dissolving them altogether. Past disinterments in Smithfield have proven this, discovering bones that were little more than mush or stains in the soil, whereas bones in dryer areas of Jamestown, even decades older than those in Smithfield, survive nearly intact.

The Smithfield sites include squares just south of the Archaearium, squares southwest of the Archaearium very close to the Seawall, squares just north of the Dale House, and squares southwest of the Pitch and Tar swamp. As mentioned before, the archaeology is focused here out of necessity due to Smithfield’s increasingly frequent flooding. This area was used as a burial ground in the 17th century, perhaps as early as the 1610s and probably ending before 1663 with the completion of the brick statehouse which was built on top of many of the graves. In the 31 year history of Jamestown Rediscovery our archaeologists have found the remains of several buildings on top of burials, which may indicate the colonists forgot they were there or that real estate was in high enough demand that they built there anyway. The short life expectancy of colonists in the 17th century may have contributed to a loss of communal knowledge regarding the location of burials.

“Where does the burial ground end?” Answering that question is the primary goal of these excavations. The greatest number of burials appear to be on Statehouse Ridge, underneath where the statehouse sat and where the Archaearium museum now sits. In the 1950s and early 2000s dozens of burials were discovered there. The frequency appears to taper off as you head south off the ridge but exactly where they stop is unknown. A burial was found early in the 20th century just outside the Dale House, on the southern edge of Smithfield, 300 feet away from the Archaearium. Whether this burial belongs to the same graveyard as those further north is unknown, but the excavations that the field school students undertook aimed to fill in the missing pieces, including finding negative space — where there are no burials — to find the bounds of the burial ground.

south of the archaearium

Just south of the Archaearium the field school students and archaeologists found four additional burials as they opened new squares heading south. During the dig here the team found window glass, pipe stems of both European and local clay, wine bottle glass, mammal bones, window lead and lead shot, English flint, and sherds of Portuguese faience, as well as other earthenwares and stonewares.

near the seawall

As with other excavations at Smithfield, the primary objective for the dig near the seawall is to determine the bounds of the burial ground centered on Statehouse Ridge. The excavations here are very close to the Seawall, just outside the iron gate bordering the Statehouse foundation ruins. No burials have been found here as of yet, and this negative space is just as valuable in the archaeologists’ efforts to define the burial ground. But the excavations here are still in their early stages so it’s too soon to say that they’re past the graveyard’s western edge.

The overwhelming majority of artifacts found during these excavations relate to the production and installation of concrete, though of a much more modern event than one of the 17th century. Over 1,000 pounds of concrete, brick, and stone were excavated by the team in June and they believe that this is evidence of two projects from the first decade of the twentieth century, the results of which can be seen just feet away. The first is the capping of the Statehouse foundations. The second is the construction of the Seawall. There were two different types of concrete in the same soil layer: the foundation cap concrete and the seawall concrete. The seawall concrete had #57 stone mixed in — the unused #57 stone was discarded in this layer as well. The foundation cap concrete had no #57 stone, and sometimes pea gravel.

The concrete caps were an effort to preserve the Statehouse’s brick foundations, shortly after their discovery by Colonel Samuel Younge. Col. Yonge was also the lead engineer for the Seawall, a structure which prevented more of the island (and with it, James Fort) from eroding into the James River. His book, “The Site of Old Jamestown” (1904), describes the state of Jamestown as he found it before he began his work.

Collapsed metal cans, a possible can key, and two nearly-intact glass pickle bottles found here by the archaeologists and students may also be evidence of the people working on these projects. A large number of modern bricks, some with mortar still attached, have also been found here. Modern bricks were used to build up two cellars of the rear additions to the Statehouse complex during these same efforts, and these may be discards from that process.

Martha W. McCartney, in her book Jamestown: An American Legacy, writes

One local resident, who witnessed construction of the concrete seawall, said that most of the men who built it earned $1.25 to $1.50 a day, whereas those who pushed the wheelbarrows containing bags of cement received an extra 25 cents. The majority of these laborers were African Americans, who reported to work each morning at 7 A.M. and typically put in a 10-hour day shoveling cement. Colonel Samuel H. Yonge of the Army Corps of Engineers, who oversaw construction, was a skillful engineer and diligent scholar whose antiquarian interests led him to study the island’s history and explore its archaeological features.

Older artifacts have also been found in this area, including late Ming porcelain, Westerwald ceramic sherds, and pearlware dating to ca. 1775 at the earliest. Cow bones, a possible Yadkin projectile point, and pipes made of both European and local clay have also been found during these excavations.

outside the dale house

A bit north of the Dale House the excavations are heading in that same direction, eventually to meet the excavations headed south from the Archaearium. A total of 21 5 x 5’s will be excavated north/south across Smithfield. In the new squares here, the staff and students have found a small posthole with a charcoal fill and a second posthole unrelated to the first. A third feature, an amorphous charcoal-filled feature was also discovered, inside of which the team found a sherd of Native ceramic. A plethora of plow scars were found by the team, speaking to the centuries of farming that occurred on the island. Two partial projectile points, lead shot, wine bottle glass, and a partial Turk’s Head pipe bowl were found here. Additionally a sherd of pearlware was unearthed in these excavations. A glass intaglio, possibly dating to the 19th century, was discovered here, debossed in reverse with the name “Dr. Franklin”, so that it would read correctly when stamped.

A possible ditch, perhaps used as a property boundary but which doesn’t align with any known boundaries, was found in these excavations. A relative lack of artifacts here may point to the soil in this area being “harvested” in 1861 to build Fort Pocahontas a few feet to the southeast.

barracks

The excavations in an area we’re calling the “Barracks Site” are occurring where they are because ground-penetrating radar (GPR) indicated the presence of a series of 6′ x 6′ anomalies. These may be related to Confederate barracks built in 1861 on Jamestown Island as part of the defenses against Union ships moving upriver towards Richmond. A recently-discovered map in William & Mary’s special collections indicates there are barracks in this general area, though the map is significantly out of scale. Once the Union captured the island in 1862, Confederate barracks were repurposed as housing for “contrabands”, enslaved persons who freed themselves by running away or swimming across the river to the Union-held territory.

Four possible postholes were discovered here this month, though they don’t appear to share an alignment that would suggest they belong to the same structure. The team has found two water pipes, one large one oriented roughly north/south and a smaller one running east/west. The purpose of the larger one is probably to drain the Fort Pocahontas area and it was likely installed in the early 20th century. Another section of the pipe was discovered previously inside the earthworks just to the south. A drain that most likely feeds this pipe is visible inside Fort Pocahontas as well. The smaller pipe used to supply water to the decorative horse trough gifted to Jamestown in 1907 for the 300th anniversary of the settlement. The trough has since been moved just outside the Yeardley House and is no longer supplied with water, but automobiles have since replaced horses as the primary terrestrial mode of reaching the island.

Roots have been found in abundance here, slowing the excavations. Additionally, the soil here has become hydric due to the long periods of saturation. This has turned the soil gray, making it difficult for the archaeologists to distinguish features from the negative space surrounding them. A ditch predating the horse trough pipe was found here, but its construction date can’t be narrowed further. Among the artifacts found in these excavations are a sherd of native ceramic, a worked lithic, a projectile point, lead scrap, a sherd of creamware (the earliest possible date for creamware being the mid 18th century), a sherd of delftware, and a nearly complete 19th century glass bottle. Because the soil is so wet, it’s not readily going through the screens used during the search for artifacts. The team is using a water hose and nozzle to help break the soil apart, a process called wet screening.

cellar

Over a hundred yards to the southeast, the field school’s final excavation area is on the property of John Howard, a tailor who patented land here in 1694. The patent described his property as bordered by the churchyard to the south and the Great Road to the east. By examining excavations from the previous 31 years of the project, Senior Staff Archaeologists Mary Anna Hartley and Anna Shackelford identified a number of ditches and fence lines that match the survey measurements on John Howard’s land grant. Previous archaeology had also uncovered portions of the Great Road northeast of the Church, allowing the team to place Howard’s property on the landscape.

This area was previously partially excavated, a 5′ x 5′ square having been dug in 1995, the second year of the project. The archaeologists and students here found the previous excavation square as well as another modern feature, conduit for fiber optic lines that provide Internet to the Memorial Church and the ticketing shed. The team has uncovered a number of features, including multiple postholes, a possible burial, the eastern half of the cellar, and parts of both a potential builder’s trench and robber’s trench for the cellar. The archaeologists will expand the excavation area to fully expose the cellar and its associated features.

The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities’ (now Preservation Virginia) “rest house” was built in this area in the early 20th century and evidence of construction from that time period has turned up in these excavations. A large pile of wire nails was found here that may relate to that structure.

The team has found the northeast corner of the cellar. Reaching the cellar fill layers, whole bricks have started to be exposed, poking through the plowzone. In the layers above, only fragmentary bricks existed. Two possible postholes have been found in the excavations here and the archaeologists are hoping to find more to see if there’s a pattern.

This site has been artifact-rich. Some of the finds include a horse tooth, pipe stems, English flint, a partial wine bottle, a gooseberry bead, a chevron bead, lead shot, a small hammer, a number of hand-wrought nails, mouth-blown glass (probably part of a wine bottle) a copper alloy buckle, two partial projectile points, a twentieth-century glass vessel, a lead seal, a sandstone roof tile, an aglet, limestone, a copper alloy aglet and many different sherds of ceramics including Frechen (possibly belonging to a Bartmann jug), delft drug jar, Westerwald, Chinese porcelain, Portuguese faience, three sherds of John Dwight ceramics (ca. 1690 being their earliest possible date), redware, Midlands purple earthenware, whiteware, and Native ceramics. The lead seal is a 4-part example, probably an alnage seal bearing a bust of George I of England. Finally a Dutch brick was found here. These were decorative and typically indicated a household of means.

Field school students and staff drove the Loop Road to the Travis Estate and were hosted by a group of National Park Service archaeologists led by Dr. David Gadsby to learn about the excavations at that site. The Travis family was one of the two largest landholders on Jamestown Island (the others being the Amblers) in the 18th century, enslaving dozens of persons of African descent to work on their plantation. These new excavations are only the latest in a number of digs the results of which have informed the successive ones. Archaeologists J.C. Harrington and Dennis Blanton were among those who helped define the Travis Estate through their excavations in the 20th century. The current dig began in 2023 during which 18 major new features were discovered, including brick foundations for several buildings and a 19th-century wagon road, the soil of which was compressed through repeated use. Dr. Gadsby’s team, which includes Jamestown Rediscovery alumni Bob Chartrand and Bruce McRoberts, has found features spanning three centuries. The Travis Estate is located a short walk off of the Loop Road.

collections

The field school students also spent a large portion of their time at Jamestown in the lab, learning how to process artifacts once they come in from the field. The curatorial staff taught the students how to wash, sort, and label artifacts, as well as pick through tiny objects found while screening or floating soil. The collections staff also instructed the students in the identification of faunal remains, environmental monitoring (temperature and humidity) of collections, X-ray imaging of artifacts, artifact photography, physical and chemical conservation techniques and more.

In addition to her field school duties, Associate Curator Janene Johnston spent much of June working on the reference collection for spurs. There are around 20 copper alloy spurs in the Jamestown collection, with only one being complete. The collection contains many examples that are just the rowel (the rotating disc that presses into the horse’s side), and many others that are just the buckle. Most of the rowels in the collection are either star or snowflake shaped. Janene will next turn her attention to the iron spur collection.

Janene has also overseen progress on the geological reference collection. Marina and Mara, two students from the geology department at William & Mary, lent their time and expertise to these efforts, confirming and identifying some of the unique rocks in the Jamestown collection. We are grateful for the continued aid provided by William & Mary’s Dr. Chuck Bailey and his students as knowledge from many disciplines is needed to piece together the Jamestown puzzle.

With the installation of the oversized storage cabinet in the Vault, Senior Curator Leah Stricker is taking to the task of filling it with artifacts, specifically ceramic vessels. Two out of the four cabinets will be filled with English earthenware, the third with European earthenware, and the fourth with stoneware, the majority of which came from states within the modern borders of Germany. The task is not a simple one. Besides the spatial constraints imposed by the cabinets and the artifacts, reorganization is difficult because of the fragile nature of the ceramics. Leah is organizing using measurements on paper rather than haphazardly placing the vessels only to find something doesn’t fit for physical or thematic reasons. The less she handles the objects the less chance there is for damaging them. The placement of these vessels is the final step in an effort that involved many hours of mending and research by several members of the curatorial staff.

Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp is contributing data to a cattle morphometric project. Led by Drs. Nicolas Delsol (University of Florida) and Martin Welker (University of Arizona), the project’s goal is to track changes in the sizes of cattle historically all over the world — other data entries have come from the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Finland, Spain, Haiti, Guatemala, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Magen took measurements of several cattle bones excavated from contexts dating from 1610-1650 and shared the data with the project team. Magen is also continuing her work on faunal remains from the fort’s first well. She has now processed over 593,000 bones from layers H, N, and W. The well, like many others at Jamestown, was used as a trash repository after its water became non-potable. And because yesterday’s trash is today’s treasure, wells are extremely valuable archaeologically.

Book hardware continues to take up much of Senior Conservator Dan Gamble’s efforts. Metal latches and catches were used to keep books closed at a time when pages were often made of vellum rather than the paper we’re used to. Vellum expands when it comes in contact with the humidity in the air, hence the need for the book hardware. The majority of the hardware is copper alloy and Dan is cleaning the artifacts prior to photographing and “pXRF-ing” them. Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF) is a non-destructive process used to determine the chemical composition of an object. Dan is continuing his research into these objects, hoping to determine where the hardware was made and if there is anything else we can learn about the books they once were a part of.

Assistant Curator Jo Hoppe is working on a Midlands Purple butter pot for inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet. The pot, made in the Midlands region of England, gets its color from the iron-rich clays of that region. Some of the joints (surfaces between two mends) of the vessel Jo is working on were showing signs of failure so she had to disassemble most of it to get to the problem spots. At that point she figured she should probably redo all of the mends, using the latest adhesive and fixing any mending imperfections. She used gaseous acetone to weaken the bonds of all the joints and then carefully pried apart each sherd. Jo is starting from the base, but because only half of the base has been found, she’s using a custom foam support. Jo wants to get the base as perfect as possible because little imperfections in the alignment of the base are magnified as you mend pieces above it. She uses her fingers to feel for imperfections in the alignment that might be missed through sight alone.

The origin of the Roman oil lamp from Jamestown (April 2024 Dig Update) has intrigued Senior Curator Merry Outlaw and Dr. Eric Lapp (an archaeologist who specializes in ancient light use and technology) for quite some time. Dr. Lapp had a hunch that the lighting vessel was manufactured in Roman Cologne (Germania Inferior) or Trier (Belgica). So, this past June, he packed his bags and journeyed to Belgium and Germany where he conducted a survey of regional museum collections in search of close parallels to the Jamestown lamp. He was not disappointed. Dr. Lapp soon discovered that the Jamestown lamp closely resembled the Cologne-made factory lamps recovered from Roman burial tumuli (mounds), sanctuaries, and villas in the region — so much so that he was able to confirm that the Jamestown lamp also came from one of the many pottery workshops located in Cologne. Once fired and ready for sale, the clay lamp was likely exported westward along the Roman road through Northern Gaul and then by ship to Roman Britain. There, it would end up on a sea voyage to the New World centuries later.

related images

- A pile of wire nails discovered in the cellar excavation area

- Field School student Calvin Boulier holds a lead seal, probably a 4-part alnage bearing the bust of George I of England.

- A close-up of the lead seal found in the cellar excavations. It is probably a 4-part example, bearing the bust of George I of England.

- An early twentieth-century photograph showing the APVA’s “rest house” circled in red. Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford used a drone to take a similar shot, showing the location of the cellar excavations (circled in red).

- Field school students and archaeology and collections staffs take a group shot at the cellar excavations. James Fort is in the rear.

- A drone shot of the cellar excavations. The 5′ x 5′ excavation square from 1995 is near the center. The yellow conduit houses fiber optic cable providing the Memorial Church with an Internet connection.

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand and former Director of Archaeology David Givens help install conduit for fiber optic cable in 2019. This summer’s excavations at the cellar daylighted the conduit once again.

- Visiting St. Mary’s City field school students listen to an explanation of the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and field school student Amelia Fahl examine modern beer bottle glass found at the barracks site. The team affectionately named the type “Budware”.

- Field school student Emily Yimer tries her hand at air abrasion. Air abrasion is a technique that uses pressurized air to propel a fine stream of particles to physically remove corrosion from artifacts.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber shares the discovery of an early 20th-century glass with a visitor.

- Field school student Calvin Boulier and Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis excavate an early 20th-century glass found in the cellar excavations.

- Visitors look on as field school student Calvin Boulier excavates an early 20th-century glass.

- Field school student Natalie White discusses the cellar excavations with a visitor.

- Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe teaches field school student Aidan Sherwin physical conservation techniques using a microscope.

- Dr. Chris Wilkins instructs field school student Amelia Fahl in the use of the X-ray machine.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas gives the weekday archaeology tour.

- The iron pipe found at the barracks site that used to feed water to a decorative horse trough

- Field school students Jordan Searcey and Molly Morgan take digital photographs as part of the process to create a digital 3D model of one of the squares at the cellar excavations.

- Field school student Aidan Sherwin shares some of the week’s finds with students, staff, and visitors.

- Field school students Julia Spencer and Jordan Searcey work with Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis and Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber to carefully excavate a square just south of the Archaearium.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith and field school student Calvin Boulier set up surveying equipment at the barracks dig site.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas instructs field school student Natalie White in the use of surveying equipment.

- Field school student Natalie White measures the height of the various layers in a unit while another student records the measurements as a profile drawing.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis holds a nearly complete glass bottle found at the cellar site.

- Chevron bead found at the cellar excavations

- The top part of an incomplete brass ring found in the cellar excavations

- A partial bowl of a Turk’s Head pipe found in the excavations north of the Dale House. One of the eyes of the anthropomorphic bowl is visible.

- A sherd of native ceramic found in the cellar excavations

- A close-up of the gooseberry bead found at the cellar excavations

- Field school student Emily Yimer and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid examine a partial pipe stem found in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens leads a lesson on artifact sorting in the lab.

- Field school students Aidan Sherwin and Calvin Boulier sort artifacts in the lab.

- Field school student Amelia Fahl cleans artifacts in the lab.

- A sherd of 18th century Chinese porcelain found in the cellar excavations

- Field school student Rosie Latham holds green glass she found while screening soil from the cellar excavations.

- Field school student Julia Spencer holds a small hammer found at the cellar excavations.

- Archaeologist and Director of the Voorhees Archaearium Museum Jamie May gives a tour of the Archaearium to field school students.

- Field school students and staff at the excavations south of the Archaearium

- Field school student Calvin Boulier screens for artifacts at the excavations just outside the Dale House.

- Field school students and staff at the excavations just outside the Dale House

- Field school student Molly Morgan shares a partial pipe stem with visitors to the cellar excavations.

- Field school student Aidan Sherwin examines a sherd of ceramic he found while screening through soil excavated south of the Archaearium.

- Field school student Sam Gallagher screens for artifacts in soil excavated just outside the Dale House.

- Field school student Natalie White holds a partial projectile point found in the cellar excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis demonstrates use of the Munsell Soil Color Charts to field school students to identify the color of excavated soil.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber explains the cellar excavations to visitors.

- Field school student Natalie White and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas discuss the excavations outside the Dale House.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discusses the excavations south of the Archaearium with field school students.

- Field school student Jennifer Wilkerson tests her aim with soil excavated from modern layers south of the Archaearium.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid supervises field school excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Field school students and staff excavate outside the Dale House.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo demonstrates use of a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) machine.

- Field school students and staff remove the initial modern layer of soil in new squares outside the Dale House.

- Field school students and archaeology staff form a bucket brigade to remove water from the barracks excavation site.

- 2025 field school students and archaeology staff

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp gives a lesson on zooarchaeology to members of the field school.

- Associate Curator Janene Johnston shares artifacts with field school students in the Vault.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp gives her “Introduction to Zooarchaeology” lecture to field school students.

- Field school students and staff introduce themselves in the Memorial Church.

- Dr. David Gadsby explains the findings of his team’s ongoing excavations at the Travis Estate to field school students and staff.

- A large fragment of English flint found at the cellar excavations. Two other pieces sit just to the right.

- Lead shot of two different sizes found at the cellar excavations

- An unknown object debossed with the name “Dr. Franklin” found in the southern Smithfield excavations

- A partial projectile point, possibly a Yadkin type, found near the Seawall

- A tray of artifacts found in the excavations just south of the Archaearium

- Conduit for fiber optic cables installed in 2019 (yellow) runs through the upper layers of the possible brick cellar excavations.

- An iron pipe is exposed at the barracks excavation site. The pipe fed water to a decorative horse trough installed in 1907.

- Ed Shed intern Faith shares an artifact she found while sorting through objects excavated from the John Smith Well.

- Ed Shed interns Faith and Nora stand with Ed Shed managers Natalie Reid (Staff Archaeologist) and Katie Griffith (Archaeological Field Technician).

- A heart-shaped copper alloy terminal that is part of a spur.

- A scallop-shaped stud of a copper alloy spur

- An ornate neck of a copper alloy spur including the rowel box where the rowel connects

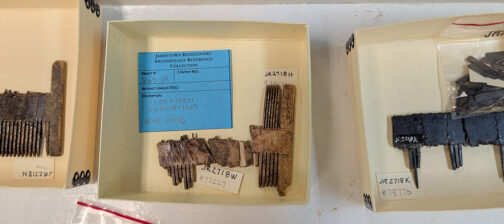

- Reference Collection for copper alloy spurs

- Copper alloy spur buckles

- Portuguese coarseware sherds under consideration for inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet

- A Portuguese coarseware jar under consideration for inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet

- Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe holds the base of a Midlands purple butter pot that she’s conserving.

- Associate Curator Emma Derry holds a bone die she found while picking through material from the fort’s first well.

- A bone die found by Associate Curator Emma Derry while picking through material from the fort’s first well

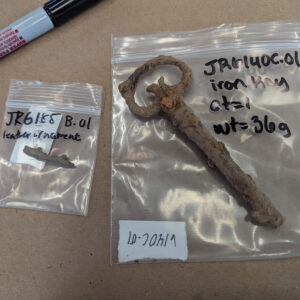

- A leather ornament and iron key found in the excavations south of the Archaearium

- A fawn sits outside the Visitor Center waiting for their mother to return.