From vibracoring to ground-penetrating radar, from Bacon’s Castle to St. Mary’s City, this year’s field school students have spent June learning a multi-disciplinary approach to archaeology in a variety of settings. The focus of their excavations remains the space next to the Archaearium, where over half a dozen burials have been found so far. However, the team has also identified the footprint of a possible early building in the same area.

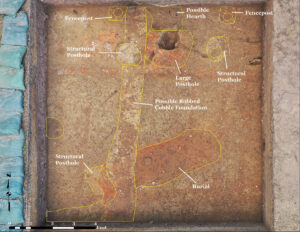

Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley is supervising the excavations where the early building’s archaeological remains were found and they remind her of Structure 187, a 10′ x 20′ addition to a fort-period building — a possible storehouse — in the center of the fort. Both Structure 187 and the new building have depressions where cobbles likely once sat, used as foundations but removed to be used elsewhere when the buildings fell into disuse. The excavations will continue in this square — the westernmost square opened by the field school students. Additional squares will also be opened up to “chase” the feature after the current squares are fully excavated, recorded, and backfilled.

More than half a dozen burials have been discovered amongst the excavation squares just in front of the Archaearium. These were expected as Statehouse Ridge — the location where the Archaearium now sits — was a graveyard likely sometime between the 1610s and 1640s. Excavations of the ridge in the early 2000s led to the discovery of over 70 burials. The diminutive dimensions of one of the newly discovered burials suggest it belongs to a small child. These recently identified graves indicate that the team hasn’t yet found the southern terminus of the burial ground. The location of the eastern edge is also unknown. However, burials have been found where the Ellen Kelso Memorial Garden now sits. Our volunteer gardeners can only put in shallow plantings, to avoid disturbing any graves. Thanks to the hard work of these master gardeners, the Ellen Kelso Memorial Garden is looking great, and the burial ground remains undisturbed.

Students and staff have found a number of interesting artifacts during their excavations so far. An exploded grenade was found this month, made of iron and very similar to those already on exhibit in the Archaearium. It’s possible these were used by Nathaniel Bacon’s men during their 1676 rebellion. A partial crucible — with melted glass still concreted to it — was found, as was a sherd of Spanish lustreware. This sherd mends with a partial vessel found over 200 yards away in James Fort’s first well. The first well was filled in prior to 1611 so this vessel dates to the first few years of the settlement. A small slate fragment found this month bears the word “first” and harks back to the slate tablet found in the fort’s first well that was covered on both sides with words and illustrations of people, plants, and animals.

The team has also found artifacts from other eras including two projectile points that likely date to the Archaic Period. Another intriguing artifact from the 19th century is a clay pipe bowl bearing the likeness of a steam locomotive. So far, three sherds of the pipe bowl have been found. This may be the same type as one found near the Mexican War battlefield of Palo Alto, Texas. Another artifact of note is a Minié ball found by Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb. Though no Civil War battles were fought at Jamestown, it was occupied by both Confederate and Union forces at different points in the conflict. This is only the seventh Minié ball in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection. Other early ceramics found in front of the Archaearium include Delftware, Borderware, Midlands Purpleware, and hundreds of pipes of both Virginian and European clays.

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) is an increasingly indispensable tool in the field of archaeology. The students were given real-world experience conducting GPR surveys just across the river at Bacon’s Castle, a 1665 brick house, one of only three surviving Jacobean Great Houses in the Americas. Bacon’s Castle is so called due to Bacon’s Rebellion, though it was built before that conflict. During the Rebellion, the house was ransacked and occupied by Bacon’s forces. At the time, the home belonged to Arthur Allen II, a prominent supporter of Governor Berkeley, Nathaniel Bacon’s enemy during the conflict. The rebels helped themselves to Allen’s food and drink, an event recorded as archaeological evidence discovered in the 1980s. Preservation Virginia — owners of both Bacon’s Castle and the 22.5 acres of Jamestown Island where Jamestown Rediscovery conducts the majority of its archaeology — was interested in locating the property’s dry wells, and the flat grassy areas immediately surrounding Bacon’s Castle were a perfect location for a GPR-101 hands-on for the field school students. Before they got started, they were given a tour of the house by Eric Litchford, Preservation Virginia’s Director of Architecture, and then the Jamestown Rediscovery staff instructed the students in the process of surveying and laying out a grid and traversing it a strip at a time in much the same way grass is mowed. Precision and accounting in these tasks will pay dividends later when the data is being analyzed. Initial parsing of the data by the team has them confident that the dry wells have been located.

The students also took trips to Colonial Williamsburg and St. Mary’s City to learn from the historians and archaeological teams there. Field schools from other archaeological projects are also traveling to Jamestown to learn from Jamestown Rediscovery. Those from Monticello, St. Mary’s City, William & Mary’s Chesapeake Archaeology Lab, and Poplar Forest are among the visiting field schools. Archaeology is a constantly-evolving science and exposure to the different methods and technologies used at other sites, and their new finds and interpretations, can be educational for students and staff alike.

Dr. David Leslie of TerrraSearch Geophysical returned to Jamestown this month to continue his waterborne GPR and vibracoring studies of Jamestown. Hundreds of feet of shoreline has been lost to erosion since the settlers first landed. Determining where the historic shoreline was can get us closer to our goal of placing historic property lines on the modern landscape. Property deeds often used the river as a boundary for delineating land parcels. Other boundaries are defined as distances from the river boundary. Adjacent properties would then use the waterfront property’s inland boundary as their starting point and so-on down the chain. Knowing property boundaries is an immensely useful tool in attributing archaeological remains to individuals. This whole process is a great example of how new technology can inform historical research which can then inform the archaeology.

During his prior visit in March, Dr. Leslie installed a 350 MHz GPR antenna in a kayak that Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown piloted in several passes just offshore of Statehouse Ridge. This survey, its locations recorded using a high-precision GPS receiver, indicated possible archaeological features in several locations just offshore. Natalie and Gabriel also kayaked clear across the river and the resultant data revealed the expected shallower areas close to shore with the main channel dropping off beyond the reach of the GPR antenna. This month Dr. Leslie installed a 200 MHz antenna on an inflatable raft which was guided by Gabriel and Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb. The team surveyed much of the same area as in March but the lower frequency antenna (200 MHz instead of March’s 350MHz) should capture data at greater depths. The team also launched their survey at low tide in an effort to get data from the deepest depths possible. It will take several weeks to process the data and we will share it in a future dig update.

Dr. Leslie’s other main push at Jamestown is his vibracoring of select portions of the Pitch and Tar Swamp. Vibracoring is the process of obtaining soil core samples using pipes that are forced into the earth with the help of vibrations. Dr. Leslie’s setup uses aluminum irrigation pipes driven into the ground by a concrete vibrating head, aided by the weight of one of the people operating the equipment. You can read more about the process in our blog post “What Lies Beneath the Swamp.” This month’s efforts have two goals in mind. The first one is to continue analyzing the Pitch and Tar Swamp in order to determine its pattern of growth over time. The second is to locate additional sections of the Great Road in the marsh to the north of the Archaearium Museum.

Once the aluminum pipes have been cut open in the lab, an experienced eye can distinguish between the soil layers that were saturated (the abundant organic material in a swamp giving these layers a dark brown color) for an extended period of time and the lighter-colored layers that were not. Dr. Leslie and Jamestown Rediscovery staff and field school students were able to push the vibrating tubes 13 feet into the swamp, often requiring the full weight of one of the students or staff to get it down. In addition to the stratigraphy analysis, Dr. Leslie will use scientific dating procedures on certain segments of the core samples. He will use radiocarbon dating on the sections of the cores that are boundaries between wet and dry vertical areas. This will let us know when the ground here was swampy and when it wasn’t, adding to our data about the timing of the growth of the swamp that the team has witnessed since Jamestown Rediscovery’s inception in 1994. Dr. Leslie will also employ X-ray fluoroscopy to measure the prevalence of mercury and lead found in the cores. Deposits of these two elements should spike with the arrival of the colonists because of their blacksmithing and other industries. A large jump in the prevalence of these heavy metals was seen in the analysis of previous core samples dating to the early 17th century. We will share the results of these new corings in a future dig update.

In the Vault, field school students and staff have taken respites from the heat and humidity outside by looking for mends in our Delft tile collection. When they find one, they are using Paraloid B-72 — a reversible adhesive — to join the sherds together. In much the same way a puzzle might be tackled, the team is organizing pieces by what’s on them — a corner (often bearing an “ox head” design), or a part of a person. Kristin Grossi, a field school student, mended a corner piece to a tile depicting a caped gentleman. Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp found mends for a tile depicting a tightrope walker. For all the students’ and staff’s hard work, there are still hundreds of sherds that have yet to be mended to other pieces. Many have little or no decoration on them, while others are corner pieces, bearing almost the same pattern for each tile. In other words, the “easy pieces” are likely gone at this point. It’s possible that future excavations will turn up more Delft sherds, either providing mends or further complicating this puzzle!

Curatorial Assistant Lauren Stephens is pouring over the sherds in our Spanish olive jar collection, making sure there are no more mends to the olive jar taken out of the Archaearium before it’s put back on display. Former collections intern Amanda Nedell wrote a blog post about her time at Jamestown this spring finding, mending, and analyzing Spanish olive jars called “Mending Olive the Jars” which you may read here.

During their time in the lab, the field school students are learning to wash, pick through, and sort artifacts. The material that they are picking comes from waterscreened samples of James Fort’s first well, also known as the John Smith Well as he ordered its construction in late 1608 or early 1609. Their help in this process is welcome as hundreds of thousands of artifacts were found inside, used as it was as a trash pit once the water turned bad. Thousands of small animal bones have yet to be processed, a record of the colonists’ diet during the Starving Time. When the students find this faunal material, it is processed by Assistant Curator and Zooarchaeological Specialist Magen Hodapp before being set aside for research by outside Zooarchaeologists Stephen Atkins and Susan Andrews.

Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins has finished his conservation of the Mount Vernon cherry bottles and they were returned by him and Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin. Chris treated the bottles for “glass disease” whereby water removes sodium from the glass. This manifests itself in the form of flaking glass. When sitting in water for extended periods, the problem gets worse as the escaping sodium entering the water raises its pH, causing the glass’ silica to also escape. This causes cracks in the bottle. You can learn about Chris’ conservation process in May’s dig update.

Chris has also been busy in instructing the fields school students how to operate Jamestown’s X-ray machine. X-ray imagery is invaluable in the conservation process, allowing the team to spot weak points in an artifact and sometimes even identify the artifact when hidden beneath centuries of rust. Locating weak sections informs conservators looking to first “do no harm” and consciously avoid poorly preserved areas of artifacts or choose different treatments altogether when they would damage the object. A conservator using an air abrader, having an X-ray image for a guide, could choose to avoid sections that only have thin amounts of original material remaining. The conservator could then take a more delicate approach in those areas. These learned techniques and considerations will be valuable experiences for any future archaeological conservators.

The students are also using microscopes to examine small artifacts and learning to use air abrasion to remove corrosion from metal artifacts. They are learning air abrasion on iron spikes that held down the gun platform of Confederate Fort Pocahontas. Our archaeologists found hundreds of these spikes left in place as the platform’s wood slowly rotted away around them. Air abraders resemble a pen, but one that shoots a precise powerful stream of aluminum oxide to remove concreted soil and corrosion. Senior conservator Dan Gamble is overseeing their efforts, providing instruction and critiquing their work. Dan has spent thousands of hours air abrading and he is happy to share his techniques and tips with the students.

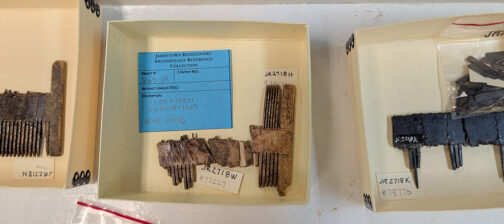

Conservation Intern Amanda Arcidiacono is overseeing the students as they conserve a portion of the collection’s window leads. Window leads are especially valuable because some of them contain dates in their center channel. These dates indicate the leads’ manufacturing year and they can help date the archaeological context in which they were found. Amanda has spent the past few months conserving window leads at Jamestown and is now passing along her experience to these students. The process includes subjecting the leads to an EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) bath, which softens them so that the window leads’ walls can be pried apart. These walls have often collapsed over time, obscuring the channel (and any dates imprinted in them). Then the students use wooden picks to gently pry away any soil or corrosion concreted to the channels. Once the channel is clean, the window lead is soaked in a water bath to remove the EDTA, prolonged exposure to which can damage the artifact. Finally the students examine the channels through a microscope, hoping to find a date. Because we record the archaeological context where each window lead was found, any dates found in the channels can then be associated with those contexts and a terminus post quem (TPQ) date can be established. Terminus post quem is Latin for “limit after which” and is a term used in archaeology defining the earliest time a context can date to. An example of this is an undisturbed context containing a 1912 penny. The TPQ for the context is 1912, meaning it could date to 1912 or later, but not before.

related images

- The excavations in front of the Archaearium

- The excavations in front of the Archaearium

- The 2024 field school students

- The field school students bring the equipment for the day’s work from the archaeology shed to the excavation area in front of the Archaearium.

- The field school students go marching in… Moving equipment from the archaeology shed to the excavation area in front of the Archaearium.

- It’s good to be the Site Supervisor.

- The outline of a child’s burial found in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- The archaeological remains of Structure 187, an early fort-period building which foundation cobbles were removed for use elsewhere. The recently-discovered building found near the Archaearium appears to also have had its foundation cobbles removed.

- Field School student Lexy Marcuson measures the depth of the excavation walls with help from Archaeological Intern Katherine Griffith and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid.

- A sherd of Spanish lustreware found in front of the Archaearium (right) mends with a partial vessel found in James Fort’s first well.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Intern Katherine Griffith help field school students Hope Clark, Madison Viars, and Richard Fallon conduct a GPR survey of a burial.

- Sherds of a Delft drug jar found in front of the Archaearium

- The exploded grenade fragment in front of other grenades on display in the Archaearium.

- Two sherds of a pipe bowl bearing a steam locomotive found in front of the Archaearium.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford holds a sherd of the train pipe bowl found in front of the Archaearium.

- A sample of ceramic sherds found while screening for artifacts in front of the Archaearium.

- A projectile point found in the excavations in front of the Archaearium.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb holds the Minié ball she found while excavating just south of the Archaearium. This is only the seventh example in the Jamestown Rediscovery collection.

- A fragment of a crucible found in the excavations south of the Archaearium. Glass is still attached to the fragment.

- A small slate fragment bearing writing found in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- A partial decorated European pipe found south of the Archaearium

- A European pipe found in the excavations just south of the Archaearium.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas assists field school student Richard Fallon with using a Munsell color chart to classify a soil sample as Archaeological Intern Katherine Griffith records the results.

- Archaeological Field Technicians Hannah Barch and Josh Barber instruct field school student Grace Blondin-Kissel in the surveying process so as to precisely record the location of archaeological features.

- Field school student Ellie Taylor discusses the excavations with visitors.

- Field school student Lainey Harding uses a ladder to get a bit different perspective on an archaeological feature she’s photographing.

- Field school student Kristin Grossi, Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, and field school student Kenna Abrams at work south of the Archaearium.

- Field school student Lexy Marcuson and Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis screen for artifacts in front of the Archaearium.

- Field school student Sofia Zate bisects a feature in the westmost excavation square in front of the Archaearium. Note the three Chesapecten jeffersonius fossils in situ.

- Chesapecten jeffersonius examples found by field school students just south of the Archaearium. This is the state fossil of Virginia.

- Field school student Grace Blondin-Kissel shares the artifacts found in her excavation square during the weekly walkabout.

- Preservation Virginia’s Director of Architecture Eric Litchford gives a tour of Bacon’s Castle to field school students and staff.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo explains the plan of action for the GPR survey of Bacon’s Castle to the field school students.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo, and Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown lay out a grid for the GPR survey of Bacon’s Castle.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo lay out a grid for the GPR survey at Bacon’s Castle.

- Staff Archaeologists Gabriel Brown and Caitlin Delmas lay out the grid for the GPR survey of Bacon’s Castle.

- Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford instructs field school students in the use of surveying equipment at Bacon’s Castle.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas instructs field school students Hope Clark, Richard Fallon, and Ellie Taylor in GPR techniques at Bacon’s Castle.

- Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown gives instruction on using the GPR machine to the field school students.

- Field school students Richard Fallon and Annabel Lawton conduct a GPR survey at Bacon’s Castle.

- Archaeologist Henry Miller gives a tour of St. Mary’s City excavations to the field school students and staff.

- St. Mary’s City Director of Research & Collections Dr. Travis Parno gives an overview of the excavations at St. Mary’s Fort.

- An aerial photograph with the locations of vibracore samples in yellow. Preservation Virginia property line is in blue.

- TerraSearch Geophysical’s Dr. David Leslie demonstrates the vibracoring process to field school students Connor DeWall and Kristin Grossi with help from Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber.

- Field school student Annabel Lawton, TerraSearch Geophysical’s Dr. David Leslie, field school student Ellie Taylor, and Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo use the vibracore process to take a soil sample of the Pitch and Tar Swamp.

- Julia Womersley-Jackman uses a jack to pull a soil sample tube back out of the swamp as part of the vibracoring process. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and field school student Lexy Marcuson assist.

- TerraSearch Geophysical’s Dr. David Leslie caps off the aluminum tube holding a vibracore soil sample from the Pitch and Tar Swamp. Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and field school students Julia Womersley-Jackman and Lexy Marcuson hold the tube.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and field school students Lexy Marcuson and Julia Womersley-Jackman carry a soil sample back to dry land for transport to the lab of TerraSearch Geophysical’s Dr. David Leslie.

- Senior Staff Archaeologists Sean Romo and Mary Anna Hartley and field school students Julia Womersley-Jackman and Lexy Marcuson walk the planks to the vibracore sites in the Pitch and Tar Swamp.

- Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown, TerraSearch Geophysical’s Dr. David Leslie, and field school students Annabel Lawton and Ellie Taylor with a vibracore soil sample taken from the Pitch and Tar Swamp.

- TerraSearch Geophysical’s Dr. David Leslie and Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo cut open one of the vibracore soil samples for analysis by field school students and staff.

- Field school student Kristin Grossi found a mend (bottom left) to this Delft tile depicting a caped gentleman.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp was able to piece together this Delft tile depicting a tightrope walker.

- Field School students Lexy Marcuson, Kenna Abrams, Lainey Harding, Grace Blondin-Kissel, and Lily Haywood take a break from the heat outside to pick and sort artifacts from the John Smith Well.

- Field school student Sofia Zate cleans a sherd of pottery in the lab.

- Field school student Kristin Grossi picks through artifacts found in John Smith’s Well.

- Public Archaeology Intern Seneca Humphries shares a tiny find with visitors in the Ed Shed.

- A visitor examines a tiny artifact she found in the Ed Shed.