Moving from terrestrial archaeology to maritime archaeology

DATE XX, 2024. David Givens, Director of Archaeology, Mary Anna Hartley, Senior Staff Archaeologist, Sean Romo, Senior Staff Archaeologist.

A 1608 map of Virginia, drawn by John Smith, depicts the region around the English settlement at James Fort. The Fort is drawn as a three-sided structure, with bulwarks at each corner, a cross indicating the location of church, and a flag-shaped fortification, or outwork, to the north. If you look closely at James Fort, you’ll see a series of dots extending from the west bulwark: a road.

Many roads across the country have Indigenous roots. While waterways were the primary thoroughfares, Indigenous peoples across the continent also created paths across the landscape between hunting grounds, villages, and nations. When Europeans arrived in North America, they adopted these paths. The path depicted on the 1608 Zuñiga map leads directly to Werowocomoco, the seat of power for Wahunsenacawh—more commonly known as Chief Powhatan—who ruled over more than 30 tribal nations in the region. It’s likely that First Peoples used this path for hundreds of years before the Jamestown settlers arrived.

The English would co-opt this Indigenous route soon after arriving. Part of this existing path would become the “Great Road” (or “Greate” – spelling varies in the 17th century). ). For the Jamestown colonists, this was the earliest road established in English North America. It was the gateway to the Virginia’s interior and a fixture on the landscape throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. In later years, the Great Road would connect Jamestown with nearby English settlements, including Middle Plantation—modern-day Williamsburg. Archaeologically, roads and paths are key parts of understanding historic landscapes. The Great Road, as an Indigenous path and then an English highway, is the way thousands of people first experienced Jamestown Island, and it defined the landscape for both groups.

Archaeology of the Great Road:

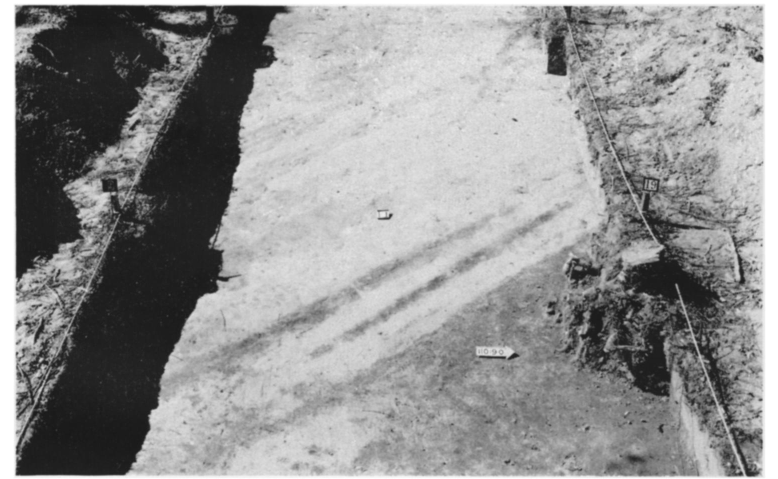

Portions of the Great Road were uncovered during the 20th-century excavations led by National Park Service (NPS) archaeologist J.C. Harrington. Harrington and his team of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) excavators—made up of local Black men—uncovered major portions of Jamestown, including buildings, property lines, and burials. His team found parts of the Great Road in two locations: one area north of the Pitch & Tar Swamp, and another near the Tercentennial Monument. More recently, Jamestown Rediscovery has used excavation and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to find additional portions of the Road, filling in some of the gaps. Unfortunately, nearly 1000 feet of the Great Road is still unaccounted for. Maps from the 17th and 18th centuries suggest its location, but the exact path of the Road—and where it crossed the Swamp—is unknown. Since the Road was a major part of both First Peoples and English landscapes at Jamestown, tracing its route is key to understanding settlement on the Island.

Less than a century since Harrington’s excavations, the Pitch & Tar Swamp has grown. Areas that were once dry land are now permanently underwater and several of Harrington’s archaeological trenches are completely inaccessible. This inundation prevents land-based—or terrestrial—archaeologists from uncovering features near the Swamp, blocking access to important pieces of our shared past. Maritime, or underwater, archaeologists might be able to investigate here, but Jamestown Rediscovery does not usually do that kind of work. Could an underwater team be brought in to help examine Jamestown’s flooded landscapes?

The Right Team:

To trace the Great Road, former JRF Director of Archaeology David Givens reached out to Elizabeth Moore and Brendan Burke, State Archaeologist and State Underwater Archaeologist, respectively, at the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (DHR). Elizabeth and Brendan recommended we bring in SEARCH, Inc (SEARCH), one of the largest private archaeological firms in the United States. SEARCH has extensive experience in both terrestrial and maritime archaeology and their maritime team has led several internationally-recognized projects, including the searches for Clotilda and Endurance. SEARCH was eager to help, and sent an expert team of underwater archaeologists, led by John Albertson, to assist with the search for the Great Road.

The first step was to identify the likely path for the Great Road between where it had been found in the 1930s and 1940s. Using historic maps from the 17th and 18th centuries (including the ones above), archaeological findings from NPS digs and more recent Jamestown Rediscovery excavations, in-depth topographical analysis, and cutting-edge GPR surveys, the Jamestown team was able to pinpoint the most probable path of the Road through the Swamp.

The SEARCH begins:

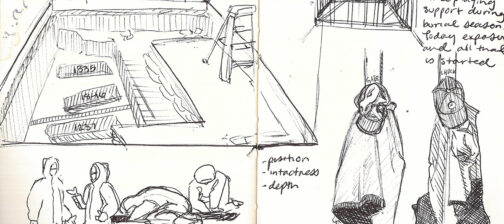

After deciding on the likely path of the road, the SEARCH team descended on Jamestown in June 2023 to deploy their advanced equipment to help with the survey. Over two days plagued by summer thunderstorms, SEARCH, DHR, and Jamestown staff, including students of the 2023 Jamestown/University of Virginia Summer Field School, conducted a survey in the western section of the Pitch & Tar Swamp. First, the combined teams had to build a survey platform that would work in the swampy environment. A sub-bottom profiler was suspended between two kayaks and a data collection station was positioned on the makeshift deck. A sub-bottom profiler uses sonar, or sound waves, to map inundated areas, not unlike a water-borne version of GPR. In theory, data collected by the sub-bottom profiler would show areas of increased compaction typical of a road’s surface. Guided by GPS, the team pushed the scanning unit back and forth across the swamp, fighting thick brush, mosquitos, and deep mud. As they moved, the sub-bottom profiler recorded detailed information about the waterlogged environment.

The environmental challenges of deploying a sub-bottom profiler in the gas-filled swamp environment pushed the limits of the machine. Methane gas bubbles and the shallow depth of the swamp hindered the data collection process, but positive results were found in at least two locations! There, “hard returns”—evidence of a solid, compacted surface beneath the mud of the swamp—were visible in the sonar data. These spots are about where the team expected the Great Road and may actually be the surviving road surface. While these limited results aren’t 100% confirmation of the existence of the road, “they are worth troubleshooting and certainly warrant further work in the swamp,” according to SEARCH lead John Robertson. This work shows that sub-bottom profiling in Jamestown’s flooded landscapes can work and can provide additional circumstantial evidence for the Great Road’s location. Hopefully, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists can continue to work with SEARCH and DHR to follow up on these tantalizing results.

Want to learn more about the project? We’re releasing two new videos on our YouTube channel soon to share the ins-and-outs of how the survey came together. Make sure to subscribe so you don’t miss the latest updates.