In the area dubbed “West Arch” (West Archaearium) by the archaeologists, features both old and modern continue to be discovered. This site is very close to the Seawall, and evidence found here this summer suggests this was a staging place for its construction. A series of postholes at five-foot intervals running roughly east/west potentially lines up with a similar pattern of postholes found just south of the Archaearium. No date has been determined for these postholes yet but they were constructed after this area was farmed as the postholes’ fill (the soil used to fill the hole around the posthole once the post was put in place) was full of soil from the plowzone. So it is likely that the line of postholes was constructed around the turn of the twentieth century, when the property was purchased by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA, now Preservation Virginia) and farming ceased. Other features discovered this month include another possible posthole unrelated to those mentioned above and a large rectangular clay feature. The latter hasn’t been fully exposed yet, but its large size would seem to preclude a single burial (a burial containing only one person). The team is going to follow the feature’s footprint north in order to define its dimensions and hopefully get a better understanding of its purpose. The primary reason for the excavations here is to define the bounds of the burial ground centered on Statehouse Ridge, just a few yards to the northeast. In this regard, not finding burials (“negative space”) is just as important as finding them. Plowscars also abound in these excavations, evidence of the centuries of farming that took place here after the capital was moved to Williamsburg in 1699. As seen elsewhere in Smithfield, a relatively flat open area northeast of James Fort bordered by the Archaearium, Yeardley House, and Dale House, the plowzone here is especially thin. The archaeologists have a theory that the soil here was taken to be used elsewhere, perhaps for landscaping purposes.

“West Arch” has been artifact rich. In addition to the multitude of artifacts found which relate to the construction of the Seawall and the preservation of the Statehouse remains dating to the early 20th century, many 17th-century artifacts have been found as well. This month sherds of Portuguese faience and redware were found here, as well as mammal bones and teeth, pipe stems, oyster shells, bird bones, and a raspberry prunt glass applique which would have adorned a drinking glass. These prunts were both decorative and provided grip for the drinker.

Moving east to the excavations south of the Archaearium, all efforts here are in preparation for the upcoming burial excavation this fall. The excavation squares here will shortly be backfilled except for the area immediately surrounding the burial to be excavated this fall. While several squares are open, containing 8 burials in total, the team is taking the opportunity to conduct several ground-penetrating radar (GPR) surveys, at 2-inch intervals, and using two different antennae (300 MHz and 900 MHz). This is a good occasion to gain additional knowledge about GPR and what it can “see” in relation to burials. The 2-inch interval is a small one and Director of Archaeology Sean Romo gave the analogy of looking at someone behind a fence. A smaller interval between surveys is akin to having thinner fence boards. If the boards were only 2 inches wide, you’d see more of the person behind them because there would be more holes in the fence. In regards to using different antennae, there is an inverse relationship between antenna frequency and effective depth. The higher the frequency, the less effective depth. But with that higher frequency comes higher resolution data. Conversely, an antenna that uses a lower frequency will be able to reach deeper into the soil, but the resolution of the data won’t be as high. By running multiple surveys using different frequency antennae, the team will be able to compare and contrast the results as they relate to the burials. The goal is to learn as much as possible about the burials without actually exposing them. Knowing the position of bones in three dimensions prior to any troweling enables the team to avoid damaging the remains should any of them be excavated in the future.

Last year’s burial excavation in this area is a good example of how GPR aids in the process. The skull of the person was raised in relation to the rest of the body. The back of the skull came in contact with the edge of the burial shaft and remained elevated as he was lowered into the shaft, in an orientation similar to someone resting their head on a pillow while reading in bed. Because the team had taken surveys of the burial prior to exposing the remains, they knew that the skull was at a slightly shallower depth than the rest of the body and accordingly took great caution as they approached its depth as indicated by radar. Unfortunately, the skull was nearly the only surviving remains of the individual, wet/dry cycles of the increasingly flooded area having turned much of the body into merely stains in the ground. It’s elevated position may have helped it survive where the rest of the body did not.

The archaeologists are taking a different approach this year in regards to the structures that will be placed over top the burial excavations. These structures protect the human remains from damage via rain, animals, and other environmental factors. Typically they’re dismantled at the end of the excavations and the wood is used for other projects. This year, the team is designing and building the structures using a more modular approach, constructing a series of 6′ x 4′ cuboids that are interchangeable and are connected using a uniform series of bolts. Additionally they will be painting the wood to help protect it from the weather, termites, and bacteria. These efforts are intended to make the structures reusable year after year, saving time and money.

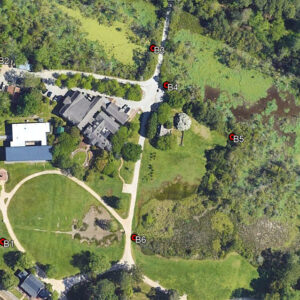

Outside contractors were on site this month performing a series of seven borings into the earth to a depth of thirty to forty feet. A series of site improvements are in the works for Jamestown, including new raised pathways to allow visitors to move around the site and berms to help protect Jamestown from the increasingly flood-prone Pitch and Tar Swamp. Before these projects can proceed, contractors came on site with their boring machine to take samples. The purpose of the borings is to determine the soil composition several feet down, the knowledge of which will help them determine compaction characteristics prior to their design and implementation work.

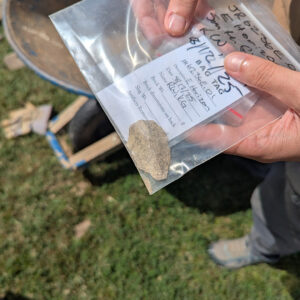

Prior to allowing the contractors to proceed with their boring, the archaeological team excavated the affected areas to make sure the holes wouldn’t damage historic features or artifacts. At one of the boring locations, just a few feet northwest of the Dale House (“B1” on the map) the archaeologists found evidence of bioturbation, that is flora and fauna that cause changes to the ground, typically in the form of roots or burrowing animals. In this case a series of holes were caused by crayfish (aka crawfish, crawdads, mudbugs). The team actually found a live one in one of the holes. This is one more reason saturated soil is bad for archaeology. Crayfish live there, and their holes can damage historic features and mix soil from different archaeological layers. Luckily in this square, the dearth of historic features meant this was not the case. Two projectile points, one possibly of the Palmer type (dating to around 10,000 years ago) and one that is unfinished were found by the team during their excavations.

Another finding at the boring location near the Dale House was a series of dark brown nodules very similar in appearance to some found in the Zuniga ditch near the Governor’s Well. They are caused by anaerobic bacteria in moist soils found just above the water table. The bacteria consumes iron and manganese as part of its metabolic processes, and then after chemical reactions inside the bacteria excretes different ions of these two elements as waste. The elements are in a dissolved form, solutes in the water in these saturated soils. But when exposed to the air, like when an archaeologist shovels off the overlying soil, oxygen bonds with the manganese and iron in the water and they precipitate out of solution as the dark brown nodules seen here. The overarching theme is that the soils here are very wet as evidenced by the presence of the anaerobic bacteria. Anaerobic soils are gray, a symptom of the lack of solid iron caused by the anaerobic bacteria’s metabolic processes. Gray soils are much harder to decipher in an archaeological context…features aren’t readily apparent, even to a veteran archaeologist. As we’ve seen they also attract water-loving crayfish that can damage archaeological features. And for soils that experience repeated wet/dry cycles, human remains situated there are turning soft, then mushy, and ultimately merely stains in the ground. These are some of the reasons we are worried about the increased flooding in Smithfield.

Curatorial Intern Molly Morgan is putting a real dent in our backlog of Native ceramic sherds. In August she analyzed several hundred more sherds, took notes, labeled, photographed, and mended them together. While finding pieces that mend is a difficult process, Molly starts by analyzing sherds that were found in the same feature. It makes sense that most or all of a broken vessel would be in the same place and so she begins there. Having said that, there are many examples of cross-mends found at Jamestown, that is pieces of a vessel that are found in different contexts. In June of last year, a sherd of Spanish lustreware was found in excavations south of the Archaearium that mended with other pieces found in the fort’s first well. The distance between the two features is over two hundred yards.

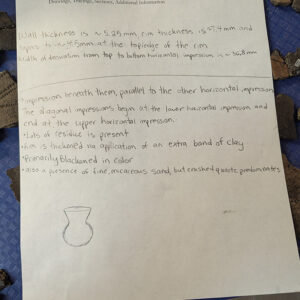

Two ceramic types Molly has been working with this month are Roanoke Simple Stamped and Potomac Creek. Seven sherds of the Roanoke Simple Stamped pot mentioned in last month’s dig update have now been mended together. These vessels tend to break apart at the seams, the junctions between the stacked coils of rolled clay that comprise them. Blackened sections both on the interior and exterior of the pot speak to its use directly in a fire, its conical shape would have been supported by rocks at the fire’s base.

Molly also found additional sherds of a Native ceramic vessel of the Potomac Creek type, associated with the Patawomeck Tribe, found in the east bulwark trench. The reconstructed pot, once displayed at the Visitor Center, shows evidence of blackening from fire — likely from cooking. Residue analysis conducted in 1999 revealed traces of both plant and animal materials. Stable carbon isotope results strongly suggest the plant component was maize, indicating the vessel was used to prepare or store mixed food resources. Nitrogen levels suggest there was either a small amount of meat or meat belonging to an animal low on the food chain, such as deer.

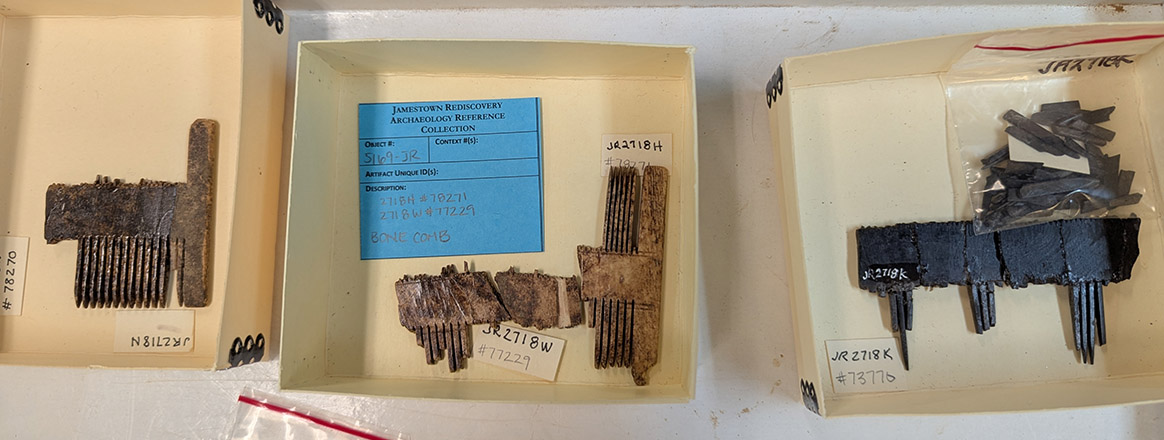

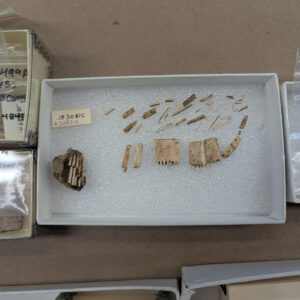

Senior Curator Leah Stricker worked on the bone comb reference collection in August. The combs, made from animal bone, were used to remove lice and nits. Leah is pulling the combs from the archive on the Vault’s second floor and cataloging them. Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp found two newly discovered pieces of one such comb while picking through material from the fort’s first well this month. Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe is lending her conservation skills to the project. She’s taking photographs and doing a condition assessment before attempting to find mendable pieces. Because of the tiny size of the combs’ teeth, mending is done under a microscope and is especially difficult. Another reason for the difficulty is that bone warps over time because of moisture loss and other environmental factors. This makes it difficult for Jo to line up the warped brittle pieces for mending. As Leah and Jo search for mends they first look for other bone comb pieces that were found in the same contexts. It’s likely that if a comb was dropped or discarded that most of its pieces are near each other. The combs were found in a variety of early contexts such as the first and second wells, Pit 1 and Pit 5. Jo is making custom foam protectors for each comb so that the fragile objects don’t move around in their boxes, possibly causing more breaks.

Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens is processing mortar and plaster from several features to accompany reports on those features written by the archaeology and collections staffs. She’s photographing these architectural materials using a uniform, reproducible lighting environment so that there can be a one-to-one comparison when considering photographs of two different artifacts. She’s also categorizing them using a Munsell color chart, a tool used by archaeologists in the field to classify soil colors. Recording all of this data is a lot of work but Lauren’s hope is that correlations may be made by analyzing it. Lauren has noted that the mortar applied between the bricks of the Governor’s Well and the Smithfield Well is similar in color. Archaeological clues suggest both wells were built in the late 1610s and similarities in the mortar might infer that it was made at the same kiln and/or by the same person. Changes in the composition of the mortar used at Jamestown over time may be able to give us clues about the availability of materials and the evolution of the colony.

In the lab, Assistant Curator Jo Hoppe is conserving Bartmann jugs and the 19th century gas oven mentioned in last month’s update. She’s making progress mending several Bartmänner but for some vessels there aren’t enough mendable sherds present for them to withstand their own weight. In these cases, Jo is building custom foam supports to bear the vessels’ weight. She is also making good progress in the conservation of a 19th-century gas oven found in several pieces during excavations south of the Archaearium last year. She has removed the corrosion on six of the pieces so far.

related images

- An overview of the excavations south of the Archaearium. Several burials can be seen in the form of dark rectangles.

- An unfinished projectile point found in the boring location square near the Dale House

- A projectile point found in the boring hole location near the Dale House

- August 2025 boring locations

- A drone shot of the boring work near the Dale House

- The archaeological staff lays boards in the path of the boring machine so that its tank tracks affects the ground as little as possible.

- The boring machine heads to its next work site. The north bulwark of James Fort is just to its left.

- A partial soil sample retrieved by the boring machine

- The crayfish found at the boring location near the Dale House.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis holds a crayfish found in Smithfield. Flooding caused by Hurricane Erin is behind her.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis scores the locations of nodules slated for XRF testing.

- Archaeologists have outlined nodules that will be tested by the portable X-ray fluorescence machine.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith digs and volunteer Patrick Shaver screens at the boring location near the Dale House.

- Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch, Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis, and Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith prepare the excavations south of the Archaearium for the approach of Hurricane Erin. The Hurricane’s eye stayed well into the Atlantic but it caused flooding nonetheless.

- The archaeological team works to protect the excavations south of the Archaearium as Hurricane Erin gets closer.

- Bone combs at Jamestown being considered for inclusion in the reference collection

- A bone comb found in many pieces. Some of the teeth are still in a clump of soil at left. The comb was found in an early fort period kitchen and cellar just east of the first well.

- A partial Bartmann jug rests on a foam support created by Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe as she mends it together.

- Pieces of the 19th-century oven. Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe has removed corrosion from the pieces in the top box. In the bottom box are fragments in varying states of conservation.

- Example labels on the interior of a Native ceramic vessel. They are applied using a reversible adhesive so as not to permanently alter the object.

- Curatorial intern Molly Morgan is taking notes for the Native ceramic vessels she’s working on. This information is entered in the collections database and will be available for future research.

- The interior of the small Roanoke Simple Stamped pot being mended by curatorial intern Molly Morgan

- A panorama of the flooding caused by Hurricane Erin, August 22, 2025

- A drone shot of the flooding caused by Hurricane Erin, August 22, 2025

- An aerial shot of the inundated barracks excavation caused by Hurricane Erin, August 22, 2025

- Flooding from Hurricane Erin inundates much of Smithfield. The barracks dig site is in the foreground.

- Captain John Smith watches Jamestown Settlement’s Godspeed replica sail upriver.

- Moments before Jamestown-Scotland Ferry passengers were forced to give a piece of eight or walk the plank.

- A great egret at Jamestown spotted by Senior Staff Archaeologist and Staff Photographer Dr. Chuck Durfor