In the field north of James Fort, Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis is finishing up excavations on one of a series of subfloor pits spread across this area at eighteen-foot intervals. Ren’s pit is the second to be excavated, and both have been amidst the same pattern of features: a posthole to the southeast, and an ash and charcoal deposit to the west. The pits have been largely devoid of artifacts save for a few beads and bones, suggesting an early date for the features, perhaps as early as 1608/09. Based on the evidence, the archaeologists believe these are living quarters, with a single posthole supporting a roof and the pits serving as root cellars. The ash/charcoal feature may indicate the location of each structure’s hearth. There are actually two postholes next to Ren’s pit: one was replaced by another in the 17th century. It appears that the post supporting the roof of this structure was rotted or damaged, and a replacement was installed during the life of the building.

A short distance to the east, what had been through to be a borrow pit is now believed to be a pug mill. Over the course of the excavations here, led by Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford and Staff Archaeologists Caitlin Delmas and Gabriel Brown, a large circular pit was revealed. In the center was a smaller circular depression. This pattern — two concentric depressions — matches historic pug mills. Pug mills were used to process clay for subsequent firing into ceramics, tiles, or bricks. The smaller inner circle held a wooden mixer. Raw clay was fed into the mixer, which was then cut and churned by a series of blades within the device. The machine was powered by a beast of burden harnessed to the mixer. The outer circle was where this animal would walk. Homogenized clay would then come out of the bottom of the mixer.

Colonial Williamsburg’s wheelwright and cooper shops recently built a historically-accurate pug mill, for use by their brickyard team. Until now, the brickyard staff had to physically stomp the clay themselves to prepare it for use in the kiln. The new pug mill will save them a lot of effort: processing clay now takes 30 minutes instead of 3 hours. Watch Colonial Williamsburg’s video about their pug mill here. Representatives from the brickyard team recently stopped by Jamestown to look at our archaeological pug mill. They agreed with our interpretation of the feature, and remarked on the similarity of our remains to what was just built at Colonial Williamsburg.

At the dig south of the Archaearium, the rest of the team — Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, and Archaeological Field Technicians Josh Barber, Hannah Barch, and Eleanor Robb — continue to find burials. The archaeologists had hoped to find an end to the burial ground, but it appears to continue farther south into the lowest-lying parts of Smithfield. Smithfield regularly floods now, something it didn’t do when Jamestown Rediscovery excavations began 30 years ago. Our archaeologists have seen what happens to burials exposed to multiple wet/dry cycles and the result is a deterioration of the human remains. So the prospect of a field full of deteriorating human remains is not a happy one for the archaeologists. One of these burials — the farthest south — will be excavated in October to assess the conditions of the remains in Smithfield.

Part of the reason Smithfield sits at such a low elevation, is that much of the original soil there was removed. The archaeologists have found that plowzone, which should be about 1 foot thick on average, is petering out as they head south. In the most recent excavation unit, only about 2 inches of plowzone survives. The current theory is that the APVA (now Preservation Virginia) scraped up this soil to fill in and landscape other parts of the site, probably around the turn of the 20th century. Farming stopped here afterward; had it continued, the remaining soil and the underlying natural layers and features would have been churned up into a new, full-thickness plowzone.

The archaeology team is preparing the 1607 burial ground for this fall’s excavations of three colonists. The burial ground is located inside the southwest corner of James Fort and contains dozens of graves of those who died in the first months of the colony. Up until the early 2000s tons of earth sat on top of this burial ground in the form of Fort Pocahontas, the Confederate stronghold protecting against Union ships headed upriver. In the first years of the 2000s the portion of Fort Pocahontas covering James Fort was removed in order to access the 17th-century archaeological resources underneath. Unfortunately that means now there is less soil separating these burials from the rainwater trickling down from the surface. Wet/dry cycles are detrimental to bone condition as the archaeologists have witnessed many times in the past. When they excavate burials, those individuals with deeper graves have less exposure to rain (as long as they’re not so deep that they’re close to the water table) and their remains are in better condition. The team has committed to excavating three burials from this area each year because their (relatively new) proximity to the surface renders them susceptible to wet/dry cycles.

Vertically between the archaeologists and the burials sits the remains of a large cobblestone foundation building measuring 92 feet in length and 20 feet in width. Thought to be one of the “two fair rows of houses” described by settler Ralph Hamor, portions of one of the building’s brick fireplaces will need to be removed in order to access the burials. This building is believed to have been built in 1611 and was constructed — perhaps unknowingly — right on top of the burial ground used four years earlier. The team has removed most of the backfilled soil from the excavations 20 years ago and has found the three burials slated for excavation right where positioning data from those earlier excavations indicated they would be. Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown is designing structures to protect the burial excavations here and south of the Archaearium from the elements. September will see preparations for the burial excavations at both sites. Excavation of overlying and intrusive features will start once the burial structures are in place, with ground-penetrating radar (GPR), photogrammetry, and surveying preceding the actual exhumations in early October. While the burial structures will prevent visitors from viewing the excavations in person, volunteers will be on hand to explain the current proceedings and answer any questions visitors may have.

Our newest employee, Assistant Conservator Joanne (Jo) Hoppe, has jumped right into her role by conserving glass found in the Governor’s Well. Jo joins us from Historic St. Mary’s City, the first English settlement in Maryland (1634) where she helped conserve a collection with many of the same types of artifacts as are found at Jamestown. The glass suffered from “glass disease” while in the well, when water causes the sodium in the glass to leach out. Now that it has been removed from its watery resting place, it’s no longer actively breaking down. But the glass has empty spaces throughout its structure where the sodium once was, making it brittle. Jo will use Paraloid B-72 to fill these empty spaces and give the glass the stability it needs to survive for another four centuries. She first will subject the glass to a bath of a B-72 solution and then use a vacuum chamber to force the air out of the empty spaces, pulling the B-72 in.

Senior Conservator Dan Gamble has finished the conservation of one of the hilts excavated from the Governor’s Well. This hilt was so heavily encrusted with rust and dirt that it wasn’t identifiable until some of the dirt was removed during on-site water screening. The final step in the conservation process was the application of tannic acid, which reacts with the iron to form a protective barrier, helping prevent corrosion. The hilt will now be housed in the Jamestown Rediscovery Center’s “Dry Room”, where humidity and temperature are kept at levels ideal for preventing iron corrosion.

Much of August for Curatorial Assistant Lauren Stephens has been spent picking artifacts from screened soil recovered from Pit 1, the first significant feature discovered by the team in 1994. Pit 1 is believed to have been a subfloor cellar for the barracks located just inside the southeast corner of James Fort. It was full of 17th-century artifacts and Lauren has proven there’s still more to be discovered. During her picking this month she has found a spangle and two tiny glass beads, one blue and one black. Spangles are similar to today’s sequins, used to adorn clothing and other textiles. The curatorial team used the pXRF (portable X-Ray Fluorescence) machine to get a chemical signature for the new spangle and it matches that of another spangle in the collection. They both are primarily silver but also have gold in them as well. This may have been an intentional gilding or may have been an additive at a time when silver was more expensive than gold. Both of these spangles are shaped like doughnuts and were cut through in one place, giving them butted ends.

Curatorial Intern Lindsay Bliss continues her flotation work on soil samples from many different contexts, including excavations as early as 2013. Flotation uses water to agitate soil samples, separating sediment from artifacts. Heavy artifacts sink during the process, while those less dense than water float to the top and are captured on a screen in another compartment of the flotation machine. Both the heavy and light fractions are then brought into the lab to be examined for artifacts. Although Lindsay isn’t picking through the fractions, she has noticed beads, bones, seeds, and Virginia Indian ceramics during her work. She’s set up under a canopy on the Seawall on the shore of the James River and has seen ospreys, eagles, and even dolphins while working through the soil samples. Lindsay will be stationed on the Seawall just east of the Dale House Tuesdays through Thursdays (weather permitting) if you’d like to come see the process in person.

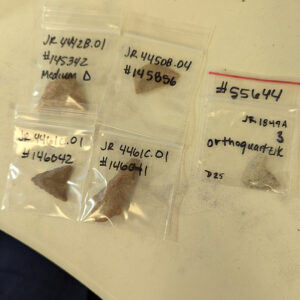

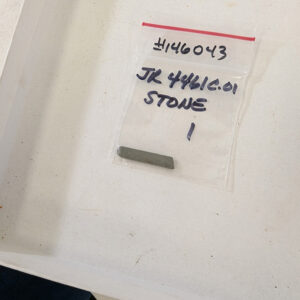

The archaeological and collections staffs are working on interim reports covering the excavations at Jamestown from 2019 to 2023. Contexts in and around the Memorial Church figure prominently in the excavations during those years and so the curators have been pulling and cataloging finds in preparation for writing. Some of these new entries include a Robert Cotton pipe bearing a shield and initials, another pipe impressed with the initials “LE”, several Virginia Indian projectile points, a large copper alloy ring — likely a bracelet, and a hematite stone, which appears to have lines intentionally etched into it. Hematite was used as a pigment for drawing or as a skin colorant; its iron content giving it a red color. Once complete, the report will join past reports on the Field Reports page.

Associate Curator Janene Johnston coauthored an article released this month on buttons found at Jamestown and at St. Mary’s Fort in Historic St. Mary’s City, Maryland. Dr. J.H. Ogborne, Curator of Collections at Historic St. Mary’s City and coauthor of the article, reached out to our collections team after the discovery of a woven metallic thread button in a midden at the Maryland site. The Jamestown collection contains eight buttons with metallic threads surrounding a wooden core. It is rare that wood survives four centuries in the ground, and some did because the metallic copper-alloy threads leached salts that prevented bacteria from consuming the cores. Others survived because they were found in an anaerobic environment (underwater) where the aerobic bacteria that consumes wood cannot live. The article discusses the composition of the buttons, the types of garments that they would have adorned, and compares the types found in both sites. You can read the full article here.

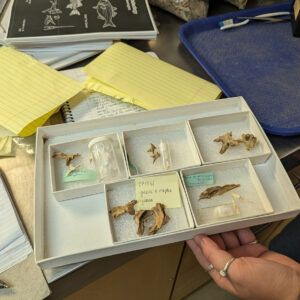

Two right mandibles (jaw bones) confirm that we have at a minimum two iguanas’ remains at Jamestown. Several other iguana bones are in the collection, found in layer “W” of the John Smith Well. Iguanas are not native to Virginia but were most likely picked up in the Caribbean as Europeans travelling to the Americas were forced to follow the direction of the trade winds through the islands on the way to the North American mainland. Whether they were eaten in the Caribbean and the bones were kept as souvenirs or whether they were still alive when they arrived at Jamestown is unknown. Watch Dig Deeper Episode 71 to learn more about the iguana remains at Jamestown. Assistant Curator and Zooarchaeological Specialist Magen Hodapp is now sorting the faunal remains of layer “N” of the same well. The colonists used the well as a trash dump once its water was no longer drinkable. Luckily for the archaeologists and collections staff, the trash includes hundreds of thousands of animal bones, leaving us a record of what they were eating in the early years of the colony — including the Starving Time winter of 1609-1610. Faunal remains found in layer “N” include shark teeth, skate/ray mouth plates, drum, sturgeon, blowfish, and sunfish bones, a dolphin vertebra with butchering marks, raptor bones, a large mammal rib with butchering marks, and a raccoon baculum with butchering marks.

Associate Curator Emma Derry was joined this month by Dr. Ashley McKeown, a biological anthropologist from Texas State University, to analyze the three burials excavated in the fall of 2023 from the 1607 burial ground. Dr. McKeown has worked with Jamestown Rediscovery for decades, helping us to respectfully learn as much as we can about these early settlers in unmarked graves. All three of the burials were oriented east/west with their heads to the west. This was the custom of European burials of the time. It is likely that all three were male, for no other reason than these settlers — having died in the earliest months of the colony’s existence — were from the first voyage and no women were among their number. These three were all young, one was approximately 11 years old, one likely 14-15, and the oldest 19-25. These estimations are based on tooth and bone analyses. The oldest was buried with a shroud based on the position of the body and the discovery of an aglet at his feet. There were no aglets in the other two burials and their body positions don’t confirm or disprove the presence of a burial shroud. The older two colonists were both between 5’6″ and 5’9″, these estimations based on measurements of their leg bones. Bone samples from the colonists’ petrous will be processed to extract DNA and then analyze it to check for colonist inter-relatedness and possibly even ancestors and descendants.

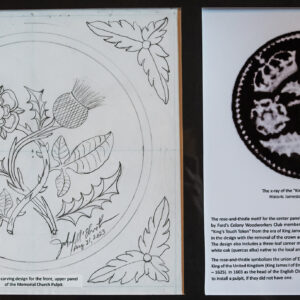

There’s a new addition to the Memorial Church exhibit! The Ford’s Colony Woodworkers spent the last year and a half constructing a new pulpit. The design is inspired by 17th-century examples found in medieval English churches. The carved panel is based on a King’s touch token and features an intertwined rose and thistle, which is affiliated with the reign of King James I, for whom Jamestown was named. The token acknowledges the union of England, represented by the rose, and Scotland, represented by the thistle. More than 60 touch tokens have been excavated at Jamestown, all in contexts dating from 1608 to 1610.

related images

- Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis surveys one of the subfloor pits in the north field.

- One of the subfloor pits in the north field. The posthole for the structure’s roof is the smaller hole at left.

- Senior Staff Archaeologists Sean Romo and Mary Anna Hartley, Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford, and Archaeological Field Technician Ren Willis discuss the excavations of one of the subfloor pits in the north field.

- Archaeological Field Technicians Ren Willis and Hannah Barch, and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas excavate a palisade wall in the north field.

- A 360 degree photo of the excavations in the north field

- Archaeological Field Technicians Josh Barber and Hannah Barch screen for artifacts from soil excavated from the north field.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo describes the pug mill excavations to members of Colonial Williamsburg’s brickyard team.

- The wooden mixer portion of Colonial Williamsburg’s pug mill. Clay is fed from the top and the refined clay comes out of the square hole at the bottom.

- The wooden blades inside the pug mill’s mixer

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley shares the plan for the 1607 burial ground excavations with the archaeological team.

- The archaeological team removes cobbles marking the location of one of the “fair rows of houses” in preparation for excavating three of the burials underneath it.

- A drone shot of the team removing backfill from the 2000s dig in preparation for burial excavations.

- Two of the tiny glass beads Curatorial Assistant Lauren Stephens has found while picking through screened soil from Pit 1.

- Virginia Indian projectile points found around the Memorial Church. These artifacts are being gathered for inclusion in the interim report covering the years 2020-2023.

- A European pipe bearing the letters “LE” found near the Memorial Church. This is one of the artifacts gathered for inclusion in the 2020-2023 interim report.

- A piece of hematite found near the Memorial Church. Note the cross marking. This is one of the artifacts being gathered for inclusion in the interim report for 2020-2023.

- A slate pencil found near the Memorial Church. This is one of the artifacts being gathered for inclusion in the interim report for 2020-2023.

- A Robert Cotton pipe bearing a shield found near the Memorial Church. This is one of the artifacts being gathered for inclusion in the interim report for 2020-2023.

- Bags of sturgeon remains from layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- A crab claw found in the John Smith Well

- Another view of the butchered dolphin vertebra found in layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- Partial skate or ray mouth plates found in layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- A shark tooth and a partial shark tooth found in layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- Associate Curator Janene Johnston shares some of the latest finds with volunteers.

- A crystal clear quartz small triangular point recently cataloged by the curatorial team.

- Associate Curator Magen Hodapp picks through faunal remains from layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- Dr. Nancy Moncrief, volunteer and Curator Emerita of Mammalogy at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, sorts through faunal remains from layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- A mammal rib bearing butchering marks found in layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- Iguana remains found in layer “W” of the John Smith Well

- Faunal remains from layer “N” of the John Smith Well.

- Zooarchaeologists Susan Andrews, Stephen Atkins, and Associate Curator Magen Hodapp review faunal remains from the John Smith Well.

- The Ford’s Colony Woodworkers pose with the pulpit, the archaeological team, and other Jamestown Rediscovery staff.

- The Memorial Church with the new pulpit at left

- The pulpit’s center panel

- Design and explanation for the pulpit’s front panel

- A storm passes north of Jamestown as archaeologists work at the pug mill site.

- Captain Brewster drills his halberdiers inside James Fort during the “Captain Brewster’s Kids” program.

- A juvenile bald eagle rests on the wooden cross erected in 1957 in memory of the colony’s early settlers.

- A drone panoramic shot of Historic Jamestowne.

- Raccoon kits curious about the archaeological goings-on.

- A storm approaches Jamestown from the southwest.