It’s kids camp month! The cellar excavation site, Vault, and lab came alive this month with the sights and sounds of our two annual kids camps. Both camps dug at an excavation site we’re currently calling “the cellar” because ground-penetrating radar (GPR) indicated the presence of a brick-lined cellar here. Trowel-in-ground excavations during this year’s field school seemed to lend credence to the GPR’s findings, daylighting several bricks in what may be the top layers of the cellar. The property is on the property of John Howard, a tailor who purchased the land here in the 1690s. Whether the structure belonged to him or was from a different time period will hopefully be answered as the archaeologists progress deeper.

July was a HOT month and so the team covered the excavation area (and the kids) with shade-providing tent canopies. Water was always available and Senior Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, manager of the kids camps, planned indoor activities for the afternoons when the temperatures reached their peaks. Each session of camp dug in two different pairs of squares, one on the north side of the cellar site, and the other on the west side. The archaeological team excavated the top modern landscaping layers prior to the start of the camps so that the kids could focus on the layers beneath. The campers spent much of their time playing in the dirt: shoveling it, troweling it, screening through it looking for artifacts, and then using wheelbarrows to take it away for backfilling when the excavations were done.

The kids excavated in the plow zones of each section, that is the depths at which farmers’ plows clawed into the earth churning up and mixing soil layers, both horizontally and vertically. Plow scars are visible as long thin lines of soil that are a different color than the surrounding earth, a symptom of the plow blade’s soil mixing. Our archaeologists find plow scars almost everywhere they dig, a testament of almost three centuries of farming on Jamestown Island. The kids found several different artifacts of note, ranging from thousands of years old to decades old. A largely intact projectile point, possibly an example of a Clagett type, could date to roughly 4000 to 3000 BCE, speaking to the thousands of years of use of Jamestown Island by Virginia Indians. Artifacts likely dating to the 17th century include a variety of ceramics such as Delftware and Midlands purple as well as firearms-related items like lead sprue. Lead sprue is the waste from shot manufacture, the leftovers after the balls are clipped from the molded lead. A 20th-century find may interest numismatists. One of our campers found a silver(90% silver, 10% copper) Standing Liberty quarter, minted between 1916 and 1930. It is heavily used, wear wiping away many of the coin’s raised details including the date that was once below Liberty’s feet.

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) enables archaeologists to learn a lot about a site without digging so much as a single shovelful of dirt. The technology allows the team to find anomalies several feet under the soil, whether they be archaeological features or tree roots. It has become an indispensable tool to the Jamestown archaeologists, allowing them to focus on promising areas and even learn details of burials such as position and depth, saving time and in the latter case, helping protect human remains. Because of its importance to the modern archaeological process, the team gave the campers instruction on both the use of their GPR machines and the science behind them. The archaeologists let them do test surveys outside at various locations across the site and in the Church Tower where the west foundation of the 1617 church lies below the floor.

In the afternoons when the temperatures were at their highest, the campers headed inside the Jamestown Rediscovery Center where the archaeologists and collections staff had lessons planned for them. One of the inside exercises was the mending of broken reproduction ceramic vessels, using the same methods and materials employed by our conservators and curators. The campers used painter’s tape to mend sherds together, a tool also used by our collections staff as a temporary adhesive. Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, our resident expert illustrator, gave the campers a lesson on the importance and methods of archaeological illustration. She shared some of the techniques she uses to portray both archaeological features and artifacts whether she’s out in the field or in the lab.

As archaeology is often a study of the past by studying trash, the archaeologists brought in (sanitary) trash from their homes to drive home the point, with the kids studying the trash and sharing what it taught them about its owners. Each camper had one group of trash, and after examining it they tried to match it to its former owner on the archaeology team. As difficult as this was, they had the benefit of living in the same time and place as the archaeologists, making recognition of the trash much easier than 400 year old artifacts.

The kids also spent time in the Ed Shed, picking through tiny material from the John Smith Well (the fort’s first) looking for artifacts. Young eyes are required for this task and so the kids were well suited for this activity. Faunal remains such as fish scales and rodent bones as well as small beads and lead shot are typical finds in this assemblage. Associate Curator Emma Derry even found a small bone die while picking through this material last month.

Iron and lead have been the focus of Associate Curator Janene Johnston in July. She is preparing the iron spurs and lead shot reference collections. Reference collections contain unique and representative examples of artifact types and are stored on the first floor of the Vault for easy access to staff and outside researchers. The other examples of these types are then stored on the second floor of the Vault, saving space downstairs. Should access to all examples of a type be needed, they can then be brought downstairs. The lead shot reference collection contains not only bullets, but also items related to their production such as bullet molds and sprue.

Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe has been busy mending ceramics this month, the majority of which are vessels bound for the oversize storage cabinet. Currently, Jo is focusing her efforts on a Bartmann jug, for which new pieces have been found. While the collections staff are always happy to find new mends for vessels already in the collection, it can mean a lot of work for the team if the new pieces belong to the interior of the vessel. In these cases existing mends will need to be taken apart before the new find can be placed where it belongs. This is the case with the Bartmann that Jo is working on. Several new sherds were found in the collection as part of a search for German stoneware, both for the reference collection, and for possible inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet. Luckily conservation staff typically use reversible adhesives when mending ceramics, and this one is no different. Jo will use gaseous acetone to weaken the adhesive and then gently pry apart the pieces to make room for the new sherds. She uses painter’s tape to give strength to newly mended sections and sets them in small plastic tubs full of sand so that they are aligned correctly as their adhesive dries.

Other artifacts Jo has been working on this month include part of a cast iron stove and an ivory finger ring. The partial cast iron stove was found in several pieces in front of the Archaearium last year and is totally enveloped in corrosion and soil. But an X-ray of the object revealed several words and numbers imprinted on the stove indicating manufacturer (A.J. Gallagher), city of manufacture (Philadelphia), and manufacture date (1858). The curatorial team did some research on the stove and found an advertisement in December 8, 1858’s edition of The Press, a Philadelphia newspaper, for the stoves. Jo is also doing a condition assessment on an ivory finger ring found in the L-shaped cellar (/archaeology/map-of-discoveries/kitchen-and-cellar/) discovered near the center of the fort. The ring is in two pieces and its size is approximately a 9.5.

Collections Assistant Lindsay Bliss will soon be floting soil samples on the Seawall again. Lindsay has been repairing and improving the floting machine and after several testing cycles has it just where she wants it. She used tiny poppy seeds as “artifacts” and after her modifications, including switching from a 1mm screen to a 0.5 mm screen, she has recovered 95 of 100 poppy seeds that went through the flotation process. Having a high recovery rate for even the tiniest artifacts is important because many of the artifacts found by the team are of a similar size to the poppy seeds. Two prominent examples are tobacco seeds, a plant of primary importance to Jamestown and Virginia, and seed beads (named for their small size). Now that the flotation machine is in excellent working order, look for Lindsay on weekdays just east of the Dale House, weather permitting. She has her work cut out for her. Over 300 soil samples, collected from a wide variety of contexts during the last ten years of the project, and each containing 10 – 16 liters of soil are in the queue for processing.

Pigs have been on the mind of Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp lately. Jamestown is participating in an isotopic study of pig bones, providing 21 samples to a team of three professors studying the origins of pigs that fed the colonists both at Jamestown and on its sister colony of Bermuda. Did the Jamestown pigs come from England? From Bermuda? Were they bred at Jamestown? 16th-century Spanish explorers populated Bermuda with pigs, later generations of which fed their rival English colonists after their arrival in 1609, shipwrecked on their way to Virginia. The Bermuda National Trust is providing five samples of pig bones found in 17th and 18th-century archaeological contexts to the study led by Dr. John Krigbaum of the University of Florida, Dr. Michael Jarvis of Rochester University, and Dr. Charlotte Andrews of the Bermuda National Trust. The samples provided by Jamestown are mostly from pre-1611 contexts, with some from excavated from later fort-period features. The study will use isotopic tests of the bones to attempt to determine where the pigs lived prior to their culinary demise. Stay tuned for more info as the research progresses.

Dr. Ashley McKeown, forensic anthropologist of Texas State University and long time collaborator with Jamestown Rediscovery, visited Jamestown this month to work with Associate Curator Emma Derry to continue their analysis of the four colonists disinterred in October of last year. Ashley and Emma made significant progress on two of the individuals from the 1607 burial ground, containing individuals (all male) who died in the first few months of the colony’s existence. The first individual was the best preserved of the four. He was between 25 and 45 at the time of his death, likely 30 or older. His mouth was full of cavities and he also had a few missing teeth. There is evidence of arthritis in his neck and possible gout indicated by lesions in his hands and big toe. He was about 5’7″ and had moderately robust muscle attachment points indicating a life of moderate physical activity. The colonist’s pelvis was in unusually good shape compared to others previously studied at Jamestown, enabling Ashley and Emma to study the clues evident on its surface.

The second colonist, an individual of 15 or 16 years old, was aged largely by the state of his wisdom teeth. They had erupted but the roots were only half formed. Wisdom teeth are an oft-used tool for aging young people as their development follows a very rigid timeline. Once they’re fully formed though they stop being as useful. Another clue that Ashley and Emma found was that the epiphyses (the round ends of long bones) of his femurs were unfused, another indicator of his young age.

Archaeological Intern Molly Morgan, a graduate of this year’s field school, is in the lab examining the tempers, surface treatments, and decorations of over 2000 sherds of Virginia Indian ceramics. Tempers are materials added to the clay to prevent or minimize shrinkage and cracking as the ceramic is fired. Tempers do this by increasing porosity, permitting moisture to escape as the heat is applied. Roanoke Simple Stamped ceramic, a common Virginia Indian ware type found at Jamestown, typically uses crushed shell as a temper. A common surface treatment for Roanoke Simple Stamped ceramic is a series of parallel lines imprinted by beating the ceramics with a small wooden paddle wrapped in leather cord. The paddling of the ceramics was not purely decorative; it was a step in the shaping and compressing of the clay prior to its firing.

One of the ongoing research projects at Jamestown is an attempt to pin down which Virginia Indian communities created the ceramics found here. Through various analyses, in this case being visual inspections and recording of the tempers and surface treatments, we hope to someday be able to pinpoint which communities were bringing their pots (and the food inside them) to sustain the colonists when they were unable to feed themselves. Sometimes the food was taken from the Virginia Indian settlements through intimidation or force as is chronicled by John Smith. Regardless of how they arrived, the goal is the same. When the ceramics are found in dateable contexts, we also add temporal data to the records.

Molly is organizing the sherds by temper, surface treatment, decoration, and archaeological context. One of the ways the surface decorations differ is by the direction in which the cordage was twisted, clockwise or counterclockwise. These twist directions leave a negative impression on the surface of the vessel when the cordage is pressed into the clay and can be analyzed. A “Z-twist” direction means the cord was twisted clockwise, an “S-twist” counter-clockwise. Archaeological studies have shown that there is a strong intra-communal tendency to use the same twist orientation and so researchers can use the presence of the other orientation to help trace (https://www.marylandarcheologymonth.org/post/finding-a-frontier-among-the-threads) interactions between different communities.

Another benefit of Molly’s work is grouping similar sherds together, sometimes finding sherds which mend or belong to an existing vessel and in other instances identifying a “new” vessel altogether. Just such a thing happened this month as Molly found mends for a unusually small pot. These pieces were found in the east bulwark trench thirty years ago, the feature being one of the earliest excavated in the history of Jamestown Rediscovery. The pot is a hand-coiled, simple stamped example with a shell temper. It bears ample evidence of being used, fire having blackened every sherd.

related images

- A pile of wire nails discovered in the cellar excavation area

- Field School student Calvin Boulier holds a lead seal, probably a 4-part alnage bearing the bust of George I of England.

- A close-up of the lead seal found in the cellar excavations. It is probably a 4-part example, bearing the bust of George I of England.

- An early twentieth-century photograph showing the APVA’s “rest house” circled in red. Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford used a drone to take a similar shot, showing the location of the cellar excavations (circled in red).

- Field school students and archaeology and collections staffs take a group shot at the cellar excavations. James Fort is in the rear.

- A drone shot of the cellar excavations. The 5′ x 5′ excavation square from 1995 is near the center. The yellow conduit houses fiber optic cable providing the Memorial Church with an Internet connection.

- Archaeologist Bob Chartrand and former Director of Archaeology David Givens help install conduit for fiber optic cable in 2019. This summer’s excavations at the cellar daylighted the conduit once again.

- Visiting St. Mary’s City field school students listen to an explanation of the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas and field school student Amelia Fahl examine modern beer bottle glass found at the barracks site. The team affectionately named the type “Budware”.

- Field school student Emily Yimer tries her hand at air abrasion. Air abrasion is a technique that uses pressurized air to propel a fine stream of particles to physically remove corrosion from artifacts.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber shares the discovery of an early 20th-century glass with a visitor.

- Field school student Calvin Boulier and Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis excavate an early 20th-century glass found in the cellar excavations.

- Visitors look on as field school student Calvin Boulier excavates an early 20th-century glass.

- Field school student Natalie White discusses the cellar excavations with a visitor.

- Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe teaches field school student Aidan Sherwin physical conservation techniques using a microscope.

- Dr. Chris Wilkins instructs field school student Amelia Fahl in the use of the X-ray machine.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas gives the weekday archaeology tour.

- The iron pipe found at the barracks site that used to feed water to a decorative horse trough

- Field school students Jordan Searcey and Molly Morgan take digital photographs as part of the process to create a digital 3D model of one of the squares at the cellar excavations.

- Field school student Aidan Sherwin shares some of the week’s finds with students, staff, and visitors.

- Field school students Julia Spencer and Jordan Searcey work with Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis and Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber to carefully excavate a square just south of the Archaearium.

- Archaeological Field Technician Katie Griffith and field school student Calvin Boulier set up surveying equipment at the barracks dig site.

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas instructs field school student Natalie White in the use of surveying equipment.

- Field school student Natalie White measures the height of the various layers in a unit while another student records the measurements as a profile drawing.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis holds a nearly complete glass bottle found at the cellar site.

- Chevron bead found at the cellar excavations

- The top part of an incomplete brass ring found in the cellar excavations

- A partial bowl of a Turk’s Head pipe found in the excavations north of the Dale House. One of the eyes of the anthropomorphic bowl is visible.

- A sherd of native ceramic found in the cellar excavations

- A close-up of the gooseberry bead found at the cellar excavations

- Field school student Emily Yimer and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid examine a partial pipe stem found in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens leads a lesson on artifact sorting in the lab.

- Field school students Aidan Sherwin and Calvin Boulier sort artifacts in the lab.

- Field school student Amelia Fahl cleans artifacts in the lab.

- A sherd of 18th century Chinese porcelain found in the cellar excavations

- Field school student Rosie Latham holds green glass she found while screening soil from the cellar excavations.

- Field school student Julia Spencer holds a small hammer found at the cellar excavations.

- Archaeologist and Director of the Voorhees Archaearium Museum Jamie May gives a tour of the Archaearium to field school students.

- Field school students and staff at the excavations south of the Archaearium

- Field school student Calvin Boulier screens for artifacts at the excavations just outside the Dale House.

- Field school students and staff at the excavations just outside the Dale House

- Field school student Molly Morgan shares a partial pipe stem with visitors to the cellar excavations.

- Field school student Aidan Sherwin examines a sherd of ceramic he found while screening through soil excavated south of the Archaearium.

- Field school student Sam Gallagher screens for artifacts in soil excavated just outside the Dale House.

- Field school student Natalie White holds a partial projectile point found in the cellar excavations.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis demonstrates use of the Munsell Soil Color Charts to field school students to identify the color of excavated soil.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber explains the cellar excavations to visitors.

- Field school student Natalie White and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas discuss the excavations outside the Dale House.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discusses the excavations south of the Archaearium with field school students.

- Field school student Jennifer Wilkerson tests her aim with soil excavated from modern layers south of the Archaearium.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid supervises field school excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Field school students and staff excavate outside the Dale House.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo demonstrates use of a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) machine.

- Field school students and staff remove the initial modern layer of soil in new squares outside the Dale House.

- Field school students and archaeology staff form a bucket brigade to remove water from the barracks excavation site.

- 2025 field school students and archaeology staff

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp gives a lesson on zooarchaeology to members of the field school.

- Associate Curator Janene Johnston shares artifacts with field school students in the Vault.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp gives her “Introduction to Zooarchaeology” lecture to field school students.

- Field school students and staff introduce themselves in the Memorial Church.

- Dr. David Gadsby explains the findings of his team’s ongoing excavations at the Travis Estate to field school students and staff.

- A large fragment of English flint found at the cellar excavations. Two other pieces sit just to the right.

- Lead shot of two different sizes found at the cellar excavations

- An unknown object debossed with the name “Dr. Franklin” found in the southern Smithfield excavations

- A partial projectile point, possibly a Yadkin type, found near the Seawall

- A tray of artifacts found in the excavations just south of the Archaearium

- Conduit for fiber optic cables installed in 2019 (yellow) runs through the upper layers of the possible brick cellar excavations.

- An iron pipe is exposed at the barracks excavation site. The pipe fed water to a decorative horse trough installed in 1907.

- Ed Shed intern Faith shares an artifact she found while sorting through objects excavated from the John Smith Well.

- Ed Shed interns Faith and Nora stand with Ed Shed managers Natalie Reid (Staff Archaeologist) and Katie Griffith (Archaeological Field Technician).

- A heart-shaped copper alloy terminal that is part of a spur.

- A scallop-shaped stud of a copper alloy spur

- An ornate neck of a copper alloy spur including the rowel box where the rowel connects

- Reference Collection for copper alloy spurs

- Copper alloy spur buckles

- Portuguese coarseware sherds under consideration for inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet

- A Portuguese coarseware jar under consideration for inclusion in the oversized storage cabinet

- Assistant Conservator Jo Hoppe holds the base of a Midlands purple butter pot that she’s conserving.

- Associate Curator Emma Derry holds a bone die she found while picking through material from the fort’s first well.

- A bone die found by Associate Curator Emma Derry while picking through material from the fort’s first well

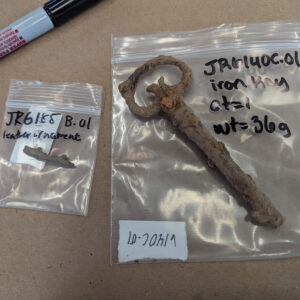

- A leather ornament and iron key found in the excavations south of the Archaearium

- A fawn sits outside the Visitor Center waiting for their mother to return.