The area to the south and west of the Archaearium is abuzz with the scrapes of archaeologists’ shovels and trowels carefully exposing the historic layers beneath their feet. This part of Jamestown has never been excavated and the team is primarily interested in finding the bounds of the burial ground centered on Statehouse Ridge where the Archaearium museum now sits. From 1663 until 1698 a massive three story statehouse and connected auxiliary buildings were built in stages. Decades prior to its construction, the high ground here was used as a burial ground, and the team found dozens of burials during the Statehouse excavations of the early 2000s. After recent excavations in the past few years, the total number of grave shafts found here is up to 132, with at least 139 persons contained within (there have been a few instances of two people buried in the same grave shaft). But where does the burial ground end? Early 20th-century archaeology just outside the northeast wall of the Dale House discovered a burial there. Does the burial ground extend all the way there, clear across Smithfield? This is the main question the team is trying to answer.

These excavations are done with a sense of urgency as Smithfield has become increasingly flood-prone and last year’s burial excavation here revealed human remains that are in exceptionally poor shape — little more than stains in the ground — likely a result of repeated wet/dry cycles. Fellow colonists in even older burials (1607) are in much better shape in the high ground of James Fort, covered by the earthworks of Confederate Fort Pocahontas and thus also protected from rainwater. So there is a desire to learn all we can from these folks before they disappear completely, whether it be from biological anthropologists examining their bones and reading the “story” of their lives embedded therein or by molecular anthropologists discovering relatedness with other colonists, folks in the Old World, or even people from the present.

In an additional major step to learn all we can about the scope of the burial ground and Smithfield more generally, the archaeological team has completed the first five of a planned 21 excavation squares in a north/south line across the area, from just south of the Archaearium to just north of the Dale House. This dig, led by Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas, and employing most of the archaeological staff, is using 5′ x 5′ squares, 75% smaller than the usual 10′ x 10’s, allowing a more rapid course across Smithfield. In the southernmost of the five units, two historic ditches were discovered, cut by modern (1930s) utility lines. These are new ditches to the archaeological record, and they don’t correspond with any known property boundaries. Just as with every other feature at Jamestown, their position will be surveyed and recorded, another piece of the puzzle that can be referenced as Smithfield slowly reveals its secrets. These squares haven’t yielded much in the way of artifacts. An archaic projectile point — over 1000 years old — was found, which speaks to the millennia of use of the island by Virginia Indians. A partial decorative pipe stem made of local (not European) clay was found, as was a wine bottle base. Another partial pipe was found during these excavations, a bowl from a 19th century reed pipe. The team has already backfilled these squares, an indication of the rapidity with which they are marching across the field. Five additional squares in the north/south line will soon go through the same cycle.

Closer to the Archaearium, excavations are proceeding on both sides of the walking path that leads to its entrance. On the east side, the team is following a brick and mortar rubble feature that may be related to one of the instances when the Statehouse complex was destroyed by fire. The running theory is that this was an area where bricks were salvaged, perhaps to rebuild the Statehouse. Plow scars are visible cutting through the rubble but the debris exists below the plow zone as well, suggesting it may be sitting in a cellar or other underground feature. The rubble caps an earlier 17th-century building found last year, with both the east and west walls already discovered. As the team expands north to follow the rubble, they should eventually find this building’s northern wall. As far as dating these features go, the archaeologists are doing a lot of relative dating as no artifacts have as yet been found that can give them a hard date. The building cuts a brick-lined burial, and brick-lined burials weren’t used by the English until the 1650s. Because the building cuts the burial, the building is newer than the burial. And finally, the brick rubble feature caps the building, so it is the newest of the three features. This month a partial wine bottle was found here which form suggests it was made in the 1680s or 1690s.

On the western side of the walkway, excavations continue on two new squares close to the Seawall. No burials have been found here as of yet, but the team has had to contend with a labyrinth of tree roots, evidence of the stately trees flanking the excavations. They have been careful to avoid damaging the roots as much as possible. Last month several artifacts were found here including a horseshoe, a partial Dutch pipe stem, as well as sherds of Portuguese faience, and Frechen and Beauvais stoneware. These excavations have been paused as a combination of rainwater and groundwater has made progress temporarily infeasible.

Dr. David Leslie of TerraSearch Geophysical, a longtime research collaborator with the Jamestown team, was once again on the island this month, this time to help conduct research funded by FEMA to devise a proper drainage system for the Memorial Church and 1680s Church Tower. He brought with him both ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and magnetometry equipment. The drainage project is designed to help preserve the two structures, with the Church Tower being the only 17th-century above-ground structure surviving on the island. But because there are archaeological resources everywhere at Jamestown, drainage can’t be installed without first getting a “lay of the land”, or in this case a “lay of the underground.” Dr. Leslie and Jamestown archaeologists used his powerful tools to add to our knowledge of the churchyard and surrounding area so that we devise a drainage system that will both help preserve the Church structures and make as little of an impact on the archaeological resources as possible. To learn more about magnetometry at Jamestown, please read March 2024’s dig update.

Dr. Leslie also lent his hand to our photographic survey of the Church itself, where Senior Staff Archaeologist Dr. Chuck Durfor and Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford are building a 3D spatially-accurate model of the Church and Church Tower also in an effort to help guide the drainage planning. One of the challenges Chuck and Anna have run into in making a photo-realistic model is photographing hard-to-reach places, particularly the sections higher than one can reach on a ladder. One avenue the team has explored is taking the shots with a drone. At present, photographs taken with a drone are not as detailed or true-to-life as those taken with a digital SLR camera, and the two proposed using DSLR shots for the sections below the roofline, accessible to Chuck on a ladder, and drone shots for the roof and higher portions of the Tower. Chuck and Anna discovered that there were just too many differences in the results to believably blend the two sets of shots. They’ve taken the direction of exclusively using the drone shots, but Dr. Leslie suggested we try a method he’s had success with on past projects, attaching a cell phone to a long pole, letting its camera take shots as needed via photo-stitching software. Chuck and Anna are in the process of evaluating the results.

As part of the “Save Jamestown” campaign to save the island and its archaeological resources from a rising James River, our staff is planning to raise the walkways that allow our staff and visitors reach the various buildings and attractions on the island. The pathways will be paved with a stone aggregate that requires a thick rock foundation. Our archaeological team is using a backhoe to sample the full depth of the current gravel pathway to see if it’s adequate to serve as the aggregate’s foundation. Preliminary findings indicate that the existing path’s rock cover is too shallow in many places and will need to be augmented prior to the installation of the aggregate.

Jamestown was happy to host Jeremy Sanchez’s English class from Surry County High School for some hands-on archaeology. Surry County is just across the James River from Jamestown, with some of our staff taking the Jamestown-Scotland Ferry every morning as part of their commute into work. Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley is one of those, having grown up in Surry County and having a keen interest in her home county’s history, she was a natural lead for a project investigating the history of Jamestown during the Civil War, during which hundreds of enslaved persons freed themselves by boating or swimming across the river from Surry County to Union-held Jamestown Island. The Union’s practice of treating escaped enslaved persons as contraband of war — effectively meaning they wouldn’t be giving them back — had the effects of freeing thousands of enslaved persons close or behind Union lines (and putting them to work helping the Union war effort) and further stressing the Confederate homefront.

Mr. Sanchez’s students were given instruction in shoveling, troweling, screening and use of one of Jamestown’s ground-penetrating radar (GPR) machines. They then went to work in two areas of Jamestown, one being the excavations just southwest of the Archaearium, and the other on the eastern edge of Smithfield where GPR revealed the presence of several square features. These squares line up where quarters for the Bedford Artillery are represented on a Civil War map of Jamestown Island held in the collections of William & Mary’s Swam Library. These quarters may be tents, or subsequent barracks built for the soldiers. When the Union captured the island in 1862, they repurposed the barracks as housing for the escaped enslaved persons mentioned previously, many of whom came from Surry County. Luckily the area was relatively dry and the students made good progress there and across the field near the Archaearium.

This month, two new storage and display cabinets were installed in the Vault. The cabinets will house large, mended artifacts that didn’t fit well in our existing storage cabinets, and were hard to see and access easily. The curatorial team has just started to fill the new cabinet with large ceramic vessels such as olive jars and butter pots, making more space for smaller objects in the existing storage cabinets. The ability to safely house and display some of the largest ceramic and glass vessels is exciting, making these amazing artifacts a highlight of the vault!

Curatorial intern Lindsay Bliss, while picking through objects from James Fort’s first well (the “John Smith Well”), found a piece of iron brigandine armor, complete with rivets. This is another of many such pieces found in the well. Jamestown’s wells were often used as trash pits once their water became unpalatable, and this well is no different. Once conserved, this piece will join the other brigandine pieces in the Dry Room, where temperature and humidity are tightly controlled to inhibit corrosion (iron oxide AKA rust).

Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens continues to work with Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley and Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford to analyze architectural materials from different locations and times at Jamestown. Of note this month is a piece of white exterior plaster from the 1617 church, discovered in a burial shaft during excavations in the Memorial Church in 2018. On the reverse of the plaster is a protruding “X” shape from where the plaster filled in scoring on the rougher brown coat of plaster it was pressed against. The scoring was designed to produce exactly this effect on the white plaster, helping it stay in place.

Dr. Chris Wilkins is conserving a series of artifacts comprised of round copper alloy ornaments set in leather. These are notable for the existence of a small amount of leather, likely surviving due to their proximity to the copper, an element lethal to the bacteria that typically consumes leather and other biological material. Archaeologists at Jamestown have found many other examples of biological materials that have survived due to their closeness to copper, including portions of a woven Virginia Indian reed mat. The artifacts Chris is conserving are likely portions of horse furniture, the gear used on a horse for either riding or use as a draft animal. Chris is mechanically removing the overburden — the soil covering the artifacts — and then will use a consolidant on the leather portions to prevent them from deteriorating further.

This month Associate Curator/Bioarchaeologist Emma Derry and Assistant Curator/Zooarchaeologist Magen Hodapp attended the annual Society for American Archaeology (SAA) conference in Denver. The annual SAA conference is one of the largest archaeological conferences in the country, making it a great opportunity to network and present on recent research.

Emma, in a session about mortuary bioarchaeology in the southeast, gave a talk about the large burial ground on the Statehouse Ridge. She discussed the previous excavations done between 2000 and 2004, patterns relating to demographics, alignments with the ridge, coffins, and grave artifacts. The presentation concluded by presenting on the most recent burial excavation of the site from last fall and general preservation concerns given recent flooding. Magen, in a session focused on historical archaeology in the southeast, presented on the current work sorting the animal remains from the First Well. It included the methods employed for sorting such a large faunal assemblage, the organizational limitations of working in a shared space, and some preliminary identifications, mostly notably the iguana remains.

In addition to presenting, Emma and Magen were able to attend other presentations and see research posters about such topics as zooarchaeological isotope research, international mortuary excavations, working under new NAGPRA policies, and current museum projects, among others. Every SAA conference is different, and with 4 full days of presentations, attending is a great opportunity for our curators to stay up-to-date with current archaeology!

Emma and Magen also visited History Colorado in downtown Denver, an institution that Jamestown Rediscovery will soon be loaning artifacts to. Several tobacco pipes and grenade fragments will be loaned as part of a future History Colorado exhibit, entitled “Moments that Made US.” This exhibit, part of the America 250 and Colorado 150 celebrations, will bring together artifacts from across America that connect to notable events in US history.

related images

- Burials discovered in the Archaearium excavations have been digitally highlighted in yellow.

- A brick rubble feature just south of the Archaearium. This might be related to one of the instances the Statehouse was burned, once in 1676 during Bacon’s Rebellion, and again in 1698 just before the capital’s move to Middle Plantation (Williamsburg).

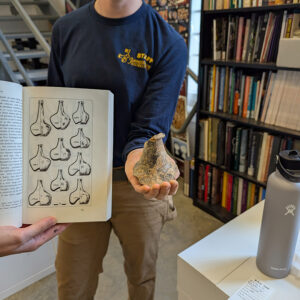

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid holds a partial wine bottle found in one of the squares just south of the Archaearium. The book at left shows wine bottle styles in the 17th and 18th centuries by year. These form trends help archaeologists and collections staff date the bottles (and possibly the features they were found in).

- Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas gives an archaeology update to volunteers and staff just outside the Archaearium as Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis conducts excavations there.

- A tangle of roots in one of the excavations squares southwest of the Archaearium. The team worked around the roots to avoid damaging the stately trees nearby.

- Screening for artifacts in the soil excavated from the squares southwest of the Archaearium

- A drone shot of the first five excavation squares in Smithfield. A bit of the Archaearium museum can be seen at the top of the photo. The Dale House is at bottom. The barracks excavation can be seen near the bottom right of the photo, covered with a tarp.

- A drone shot of the first five excavation squares in the Smithfield dig

- The excavation squares in Smithfield. The Dale House is in the rear of the photo.

- The Smithfield square containing network cables and utility pipes (not yet exposed but contained in the scored mottled trench)

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discusses the excavations in one of the Smithfield squares with Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch.

- A drone shot of the first 5′ x 5′ excavation squares in Smithfield

- Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown and Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber carefully trowel away inside one of the Smithfield squares.

- The archaeology team excavates the first five 5′ x 5′ squares in Smithfield.

- The Smithfield excavations

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber makes and records measurements related to one of the excavation squares in Smithfield.

- Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley screens for artifacts in soil excavated by Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis.

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis scores the stratigraphic layers in one of the Smithfield excavation squares as Senior Staff Archaeologist Anna Shackelford looks on. The pipes traversing the square were installed in the 1930s and the network cables in the 2000s.

- Archaeological Field Technicians Hannah Barch and Josh Barber record measurements of the excavations squares in Smithfield.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo shares some recently found artifacts with visitors.

- The archaeological crew hold a tent to provide shade for overhead record photography done by drone. The drone is visible at top coming in for the shot.

- Archaeological Field Technician Eleanor Robb and Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid score features prior to record photography in one of the Smithfield excavation squares.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid at work in Smithfield

- The team at work in Smithfield

- A partial pipestem made of local clay found during the Smithfield excavations

- A pipe bowl found during the Smithfield excavations. This is a 19th-century reed stem pipe.

- A glass bottle base found in the Smithfield excavations

- The Smithfield wine bottle base after excavation

- Staff Archaeologist Ren Willis conducts a GPR survey of the grounds north of the Church Tower and explains the process to some visitors. Ren is using a GPR machine brought by Dr. David Leslie of TerraSearch Geophysical.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch review ground-penetrating radar (GPR) data of the area north of the Memorial Church with Dr. David Leslie of TerraSearch Geophysical.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo uses ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to check for any underground features prior to testing of the depth of the gravel pathway.

- Jeremy Sanchez’s English class from Surry County High School at the Bedford Artillery barracks site

- Director of Public & Youth Programs Mark Summers gives an overview of Jamestown’s history to Surry County High School students.

- Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid examines a partial pipe stem found by a Surry County High School student while screening southwest of the Archaearium.

- Visitors investigate the finds of a Surry County High School student as she screens for artifacts.

- Backfilling the north field excavations

- Already-conserved brigandine armor in the collections dry room

- Assistant Curator Lauren Stephens holds a piece of interior plaster from the 1617 church. This side would have faced the interior of the Church.

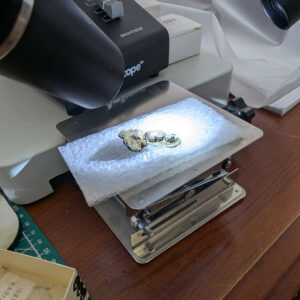

- A copper alloy and leather object, likely horse furniture, under the microscope for conservation by Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins.

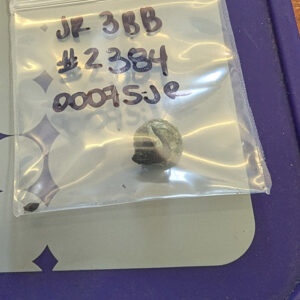

- A copper alloy object with a shred of leather still attached. This is one of the objects — thought to be part of horse furniture — Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins is in the process of conserving.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp helps visitors to the Ed Shed find tiny artifacts from objects excavated from John Smith’s Well.

- Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp gives the daily Archaeology Tour.

- Grass is planted and straw laid down after the backfilling of the north field excavations.