This year’s Archaeological Field School has begun and it’s “all hands on deck” just in front of the Archaearium. Seven 10-foot by 10-foot squares have been opened up by the students and they are carefully digging through mostly modern layers at this point. Landscaping fabric and gravel have met the students’ shovels, but it’s all part of the process for an island that has been worked and reworked many times since the settlers first landed. In one of the squares, students have hit a brick and mortar layer that could be related to the 17th-century Statehouse that once stood just a few feet away. The excavations in this square have yielded pipe stems, bone, lead, glass, and sherds of earthenware. Burials are likely to be found here as the students go deeper. Over 70 burials have been discovered just to the north, dating to the first half of the 17th century. Should additional burials be found, their coordinates will be recorded and then they will be left in place.

The field school students will soon be divided into teams and then rotated so that they get a variety of real-world archaeological experiences here at Jamestown. One team will continue the dig in front of the Archaearium, guided by Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford and Archaeological Field Technician Hannah Barch. Another will join Senior Staff Archaeologist Sean Romo on the other side of Smithfield where ground-penetrating radar (GPR) suggests there are three 6-foot by 6-foot buildings. These could possibly be Civil War barracks or shelters for contraband (enslaved people who escaped into Union-held territory). A Civil War-era map in William & Mary’s special collections library indicates that there were many buildings on the island built to house Union soldiers and these could be among those number. Sean’s team of students will hopefully shed some light on the GPR findings with their shovels, trowels, and screens.

A third excavation area, led by Senior Staff Archaeologist Mary Anna Hartley, will explore the area just to the west of James Fort’s north bulwark. The team is looking for evidence of the expansion of the governor’s house in the late 1610s by Deputy Governor Samuel Argall. A GPR survey of the area that was conducted in January was inconclusive, the results muddied by tree roots and the Confederate earthworks. The discovery of the Governor’s Well two years ago so close to this area has kindled renewed interest in the Governor’s House and its possible expansion. Mary Anna and her team will open two excavation squares here, just outside James Fort’s western palisade.

Excavations will also take place adjacent to the Godspeed Cottage, led by Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown. A GPR survey of this area indicates the presence of a large metal object and several possible graves. The Cottage has been used in a number of capacities over the years. It’s currently used by Jamestown Rediscovery’s archaeological team as office and meeting space. Prior to that it was the residence of Bill Kelso, former Director of Archaeology, and his wife Ellen. This property was owned by Robert Beverley, burgess and clerk in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and author of The History and Present State of Virginia (1705). Perhaps the GPR data indicates evidence of Beverley’s residence, or something more modern.

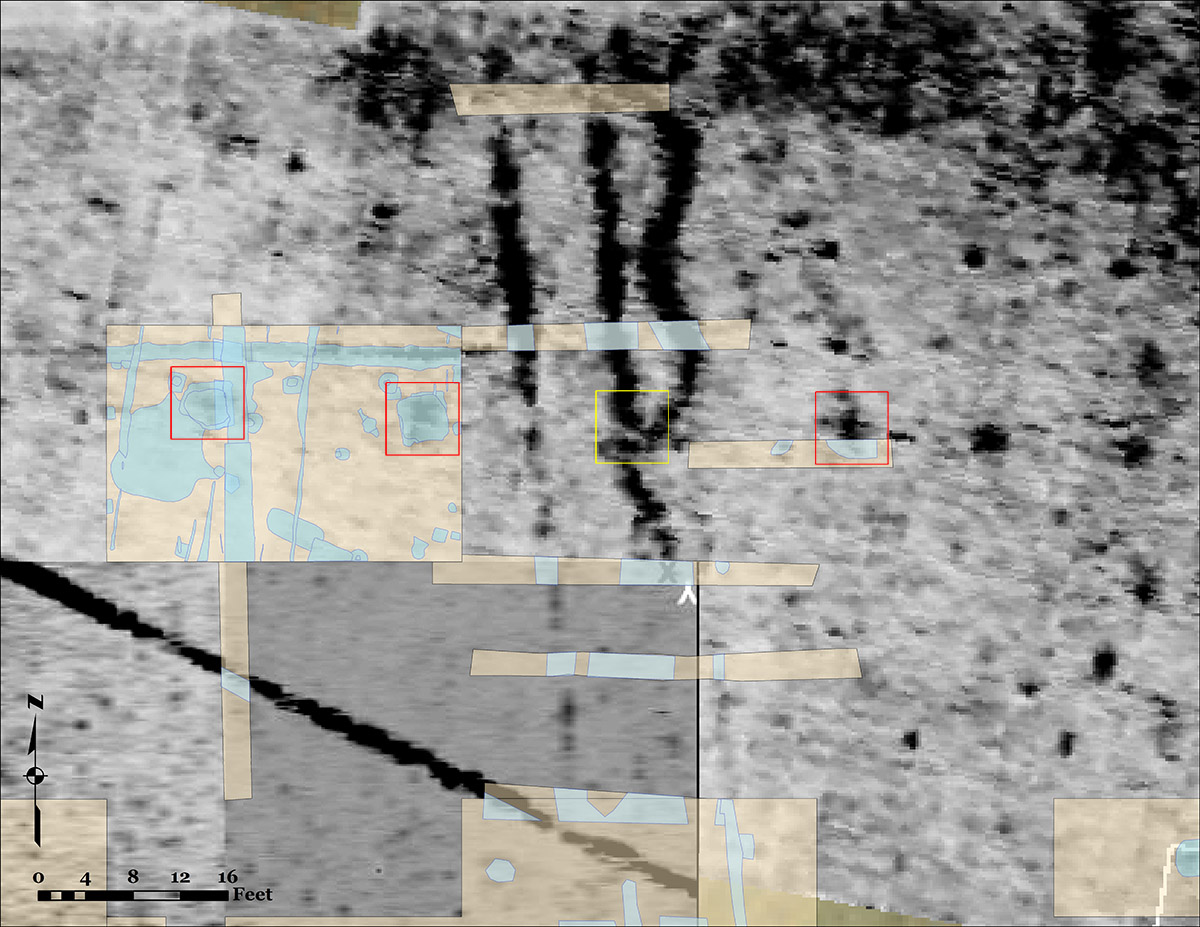

While the north field excavations have been put on pause now that the field school is in session, the findings there are looking more and more promising. When looking north from the walking path, three subfloor pits have been found at regular intervals. For the two western ones where the surrounding area has also been excavated, an area of ash/charcoal is evident just to the west of the pit, and a posthole on the east side. These may very well be dwellings, with the ash/charcoal layer indicating a source of fire, the pit used for storage (possibly for food as the lower temperature underground would have helped preserve it), and the single posthole may have supported a roof. The eastmost pit was only partially excavated in 2002, and its surrounds have yet to be explored. Once that is complete, we’ll be able to see if the same ash/charcoal/posthole pattern is evident there. Between this eastmost pit and the others to the west there is an unexcavated area where another pit should be if the same spacing holds true.

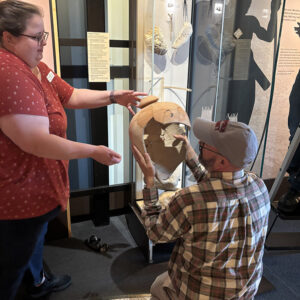

In the Vault, Curatorial Assistant Lauren Stephens and Curatorial Intern Amanda Nedell continue their work on Spanish coarseware olive jars. Sherds of this ceramic ware type have been found in a variety of fort-period contexts, and the crossmending process that Amanda is working on will help us to better understand how many olive jars were present at Jamestown, their sizes and shapes, and possibly what they were used for on the site. One of the most complete olive jar vessels is on display in the archaearium museum. Earlier this month, staff removed it from its museum case in order to check for additional mends, update the database information for the ceramic vessel, and ensure the mends are secure. Once the large vessel was in the lab, Amanda found an additional mend among the dozens of ceramic sherds in the long term storage archive. Lauren and Amanda carefully disassembled the jar, and soon it will be reassembled and back on display with its additional sherd mended into place.

Lauren and Amanda are also testing several of the olive jar sherds using pXRF (portable X-ray fluorescence). They are interested in learning about the glazes on the interior of some of the jars, and the pXRF machine will allow them to find out exactly what they are made of. The glaze’s molecular makeup could give clues as to where the vessels were made and maybe even what they were built to carry. Lauren and Amanda are also conducting pXRF testing on the exterior of some of the sherds to see if there was anything applied there. pXRF is non-destructive, so the process can be used liberally on artifacts without fear of harming them. To learn more about how the pXRF process works, read December 2023’s dig update. Amanda is working on a blog post about her internship working on Spanish coarseware that we will share in next month’s dig update.

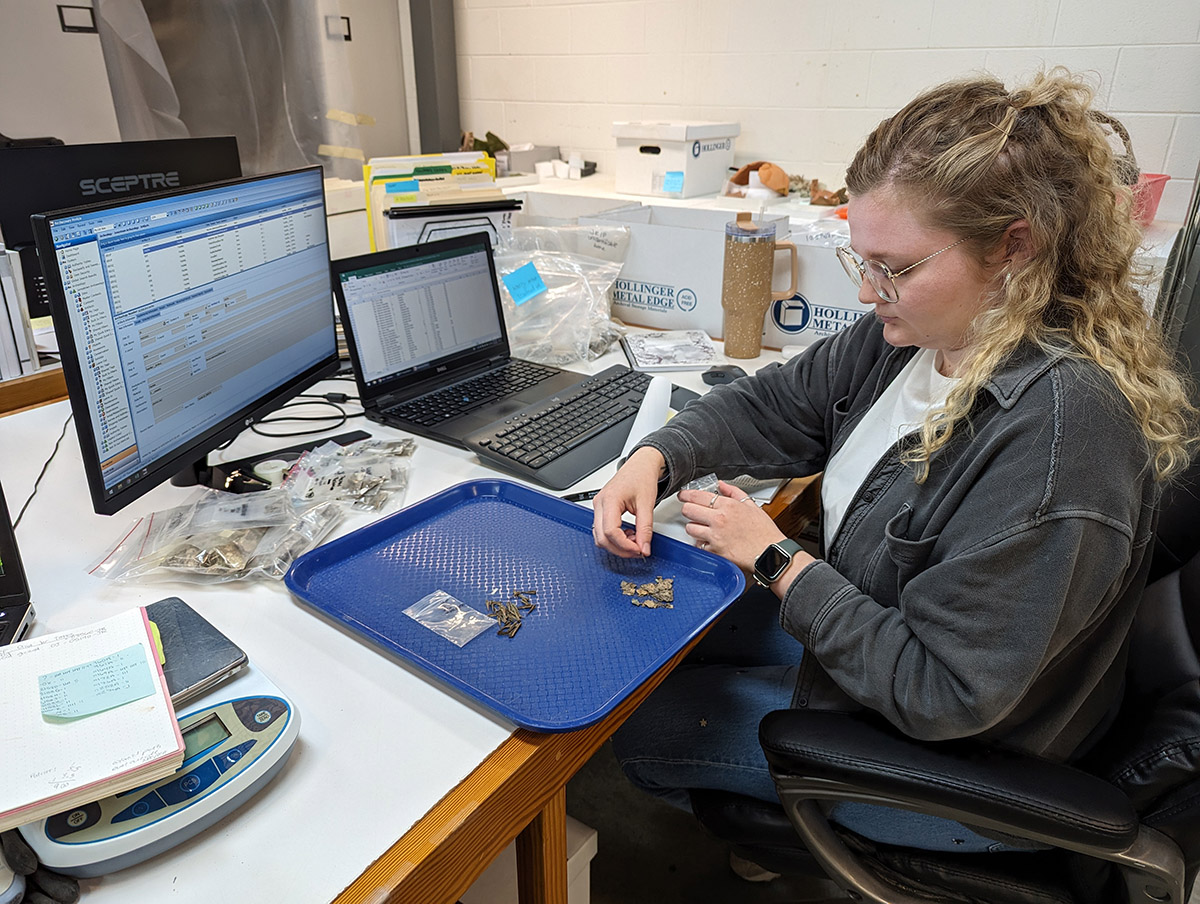

The curatorial team has completed processing all of the water-screened material from the Governor’s Well. Their next task is to catalog these artifacts and then work with the archaeological team to determine what the location of these artifacts within the well can tell us about the well’s life and the settlement’s in the late 1610s. Was the well filled in all at once? Can the type of the artifacts, presumably deemed trash by the colonists, give us insights into what they were eating or what industries they were involved with? Conservation and curation of these artifacts will ensure that they can be part of these analyses now and in the future.

Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin and Senior Curator Leah Stricker travelled to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia this month. They went to Penn for two reasons — one was to drop off material from an impacted tooth of a young boy from Jamestown to learn more about the material. Preliminary research suggests that botanical material survived inside this impacted tooth which could help us better understand the boy’s diet and his life before and during his brief, tragic stay at Jamestown. Initial analysis of the impacted material indicates that both Old World (wheat) and New World (corn) botanicals are represented. The researchers at Penn will conduct further analysis to identify as many of the components as possible.

While Michael and Leah were there they also gave a lunchtime lecture to students in the dental school, who are part of the Forensics Study Club. Michael covered the history of Jamestown and the context of the boy’s burial, and Leah covered archaeobotany and what it can tell us about life 400 years ago at Jamestown.

Animal bones from Jamestown contributed to a publication that has just come out, entitled The Dogs of Tsenacomoco: Ancient DNA Reveals the Presence of Local Dogs at Jamestown Colony in the Early Seventeenth Century. Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin, Director of Archaeology David Givens, and Senior Curator Leah Stricker are co-authors.

This publication is part of an ongoing collaboration with the primary author, Dr. Ariane Thomas. Dr. Thomas just recently completed her PhD at the University of Iowa. She originally reached out to us because of an interest in better understanding the genetic history of European dog breeds. Her first investigation of about 9 bones from our collection revealed that at least 3 dogs at Jamestown had indigenous ancestry. A Washington Post article published a little over a year ago detailed some of these findings.

Dr. Thomas’ work in this paper reveals that at least 6 dogs at Jamestown had indigenous ancestry. Her work presented here is focused on the mitochondrial side of the dogs’ DNA. This means that right now, the data is telling us that the dogs were born from mothers that were indigenous. However, this leaves open the possibility that early dogs at Jamestown were the result of indigenous and European dog interbreeding — something Dr. Thomas is hoping to better understand through additional genetic analysis.

Her colleague at the University of Iowa and coauthor on this paper, Dr. Matt Hill, has also written a paper discussing the dog bones from Jamestown, focused on the non-genetic aspects of the dogs — more about things like what sizes they were, how many dogs are represented by the collection, etc. Dr. Hill’s paper hasn’t been published yet, but we will share it when it is.

This month we’re happy to welcome our new Assistant Curator/Zooarchaeological Specialist Magen Hodapp to the team. Magen joins us all the way from Arizona, where she previously worked at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, curating National Park Service artifacts and working in the Faunal Analysis Laboratory. She received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in anthropology, both with an emphasis in archaeology, from Northern Arizona University. Her master’s thesis focused on a group of over 800 bone tools dating from 800 to 1200 CE from 6 different sites in northern Arizona, housed at two curatorial locations in Flagstaff. She identified the animals that they belonged to and studied usewear patterns and other evidence to determine what they were used for. Her thesis argued for the viability of using legacy collections for archaeological research as an alternative to inherently destructive archaeological excavations. Magen is getting her feet wet at Jamestown by cataloging faunal material from Pit 1, the first significant feature excavated by the team in 1994.

The conservation team is also excited to welcome Conservation Intern Amanda Arcidiacono to the lab. Amanda is a graduate student from the University of Maryland working toward her master’s in historic preservation. During her internship at Jamestown, she will be doing conservation and Reference Collection development for window leads. Like those most recently found in the Church Tower, window leads held glass window panes in place. Of particular interest to archaeologists are the dates and initials sometimes impressed into the interior milled channel of the lead fragments by a glazier’s, or window-maker’s vise. The initials were meant to identify the glazier, but the dates are what is most helpful in archaeological contexts, as they are another tool that archaeologists can use to date features in which they are found.

To avoid inhaling or ingesting the toxic metal, Amanda dons gloves and a mask before beginning her work. She is soaking the leads in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) to make them more pliable. This will allow her to open the leads that have collapsed, thereby revealing any possible initials and dates in their channels. After soaking them and gently prying them open, she painstakingly removes any foreign objects stuck to the lead, using a variety of brushes and picks, her favorite tool for this task being a porcupine quill. She tests her entire course of conservation on a single lead, using it as a sort of guinea pig so that if there are adverse effects to her treatments only one artifact is affected. Luckily there need be very little guesswork in her conservation as she is guided by Senior Conservators Dan Gamble and Dr. Chris Wilkins, both of whom have extensive experience conserving lead. She is taking before and after photos of each of the artifacts and is also working with Senior Curator Leah Stricker on the pre-conservation prioritization process, which helps to determine which window leads will be worked on during her internship.

You may have heard about the recent discovery of two 18th-century glass bottles filled with still-plump cherries excavated from the Mansion cellar at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. This month Historic Preservation at Mount Vernon’s Principle Archaeologist Jason Boroughs and Curator of Preservation Collections Lily Carhart called in the assistance of Jamestown Rediscovery’s conservation team to help stabilize the fragile glass bottles that had been buried for more than 200 years.

Glass is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture from the soil when it’s buried in the ground. That moisture alters the chemical makeup of the glass, leading to flaking and cracking. Glass conservation can be complex, so JRF Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins will spend the next few weeks stabilizing and conserving these two bottles.

The deterioration on these bottles tells trained conservators like Chris that they’ve experienced repeated damage-causing events. Mount Vernon has experienced many hurricanes, in historic as well as modern times, that resulted in flooding. As the bottles are exposed to large amounts of moisture from these events, sodium is extracted from the glass, which creates the flaky gel layers. This is actually the glass breaking down and if left to continue, the process will eventually eat away at the entire glass structure.

To protect the glass from further damage, Chris started off by consolidating the gel layers and glass using a solution of a chemical called B-72 diluted with acetone. This will strengthen the deteriorating layers and will allow Chris to move on to the next step in the conservation process.

related images

- Senior Staff Archaeologists Sean Romo and Mary Anna Hartley give an archaeological tour of Jamestown to the field school students.

- Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens talks to the field school students about the process artifacts undergo after coming in from the field.

- Dr. Chris Wilkins introduces himself and explains his duties to the field school students.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker and the field school students stand in front of the Jamestown collection of delft tiles. This is the “before” photo as the students will be mending these sherds to create more complete tiles as part of their curatorial duties. An “after” photo of the students and the tiles will be taken near the conclusion of the field school.

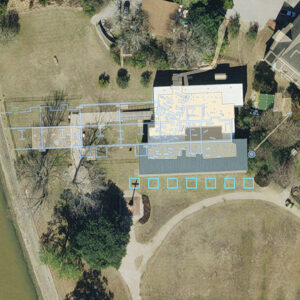

- The current field school excavations are outlined in aqua just south of the Archaearium. The 17th century statehouse foundations and other features (including burials) are colored in light blue. Excavated areas are a tan color.

- Field school students and staff excavate their squares in front of the Archaearium museum.

- A view of the field school excavations in front of the Archaearium museum

- A field school student explains the excavations in his square to staff and other students.

- Staff and students examine some of the artifacts found by field school students while screening through excavated dirt.

- Curatorial Assistant Lauren Stephens and Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin remove the olive jar from the Archaearium to mend the newly found sherd.

- A sherd of a Spanish coarseware vessel being prepared for pXRF analysis. The dark green glaze is on the interior of the vessel.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker gives a presentation on archaeobotany to dental school students in the Forensics Study Club at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Conserved window leads with visible milling marks