Director of Archaeology David Givens and Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin traveled to the University of Connecticut this month. The purpose of the trip was two-fold. They brought bone samples from the three colonists excavated this fall for DNA extraction and analysis by Dr. Raquel Fleskes at UConn’s Bolnick Lab. They also met with Dr. David Leslie who is analyzing the vibracore samples he took at Jamestown in October 2022. In a rather wet trip coinciding with a nor’easter that saw the closing of UConn for the day, the two directors first dropped off samples of petrous bone with Dr. Deborah Bolnick. Dr. Bolnick is an anthropological geneticist and she and Dr. Fleskes, an expert in molecular anthropology, make up the team who are extracting and analyzing DNA from Jamestown. The petrous is a section of the temporal bone that is especially dense and preserves DNA better than any other skeletal structure in the human body. As such the Jamestown Rediscovery team selected samples from the petrous of all three colonists for processing by the UConn team. The DNA extraction and analysis will take several months.

David and Michael also met with Dr. David Leslie who is leading the team extracting and analyzing vibracore samples from Jamestown with the hopes of understanding sea level rise and anthropogenic changes to the landscape. Dr. Leslie sat down with the two directors and discussed the initial analysis. For the samples taken from the swampy areas to the north of James Fort, the cores suggest that the saturated soil there is a new condition. The samples show that there is no thick organic buildup from the swampy areas that would be indicative of the presence of a swamp over several decades or centuries. As photographic, archaeological, and anecdotal evidence suggests, the growth of the swamp to the north and west of the fort is a relatively new phenomenon. David and Michael, both of whom have worked at Jamestown for close to thirty years, remember the swampy sections being grassy and solid enough that they were mowed along with the rest of the property. Aerial photographs from the 20th century also support the idea that the growth of the swamp is recent. Archaeological excavations were performed in the 1940s in areas that are now permanently saturated. The archaeological team is battling climate change daily both in the form of more intense and frequent rain events that cause archaeological resources to decay and racing against the clock to excavate features before they’re swallowed by the encroaching swamp.

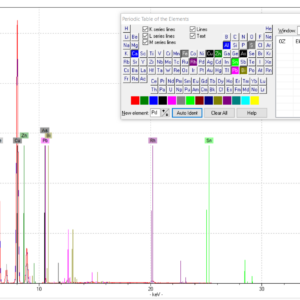

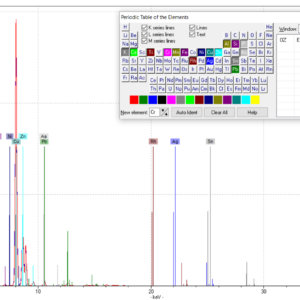

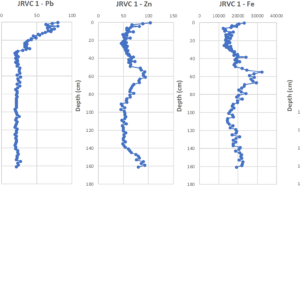

Dr. Leslie’s research is also being used as another tool to investigate the changes made to the landscape by Europeans. The core samples are about 160 cm in length (~5 feet, 3 inches) from the surface downward and pXRF (portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry) samples were taken every centimeter until 50 centimeters deep at which point samples were taken every 2 centimeters. The pXRF process uses X-rays in a sort of call-and-response process whereby X-rays are beamed into the sample and the elements in the soil emit X-rays back. Each element has a characteristic X-ray response and this is used to identify the makeup of the soil. Analysis is currently underway but a distinct introduction of lead into the soil can already be seen that may be evidence of glassmaking or metallurgy nearby. 13 cores were taken at Jamestown from a large sampling area in an effort to get a baseline for the site before reaching any conclusions.

Inside the Church Tower the team is preparing for excavations prior to the installation of a glass floor and roof. The glass floor will allow visitors to see the archaeological resources beneath, including the builder’s trench for the Tower itself and also a section of James Fort’s 1607 eastern palisade wall. The roof, the first for the Church Tower in over 200 years, will protect the lower-fired interior bricks, which were never meant to be exposed to the elements. The roof will be made of glass and will be perched slightly below the top of the Tower, thereby preserving its current iconic shape. Stemann Pease Architecture designed the roof and has also created a series of renders showing the evolution of the Church through the years (images pending). The archaeologists are working on running electricity into the Tower for lighting and a fan to prevent mold growth on the archaeological remains once the glass floor is in place. Excavating a section of the fort’s original wall is exciting for the team as is investigating the Church Tower’s builder’s trench. The Tower has long been thought to date to the 1680s but we’ve been unable to pin down anything more exact. A builder’s trench allows people to get below the surface to build the part of a structure that is underground, in this case the Tower’s foundation. On occasion archaeologists will find dateable objects in builder’s trenches, dropped in there while the trench was open by one of the people at work. We are hopeful that such an object will be found during these excavations so that we can more concretely nail down the Church’s construction period.

The ground surface of the Church Tower is now exposed in preparation for the excavations. The western foundation of the 1617 church is prominently exposed as is a large dark area, likely part of the charred remains of the previous church tower, a wood and plaster structure that collapsed after being put to the torch on September 19, 1676 by Nathaniel Bacon’s rebels.

Due to a National Park Service requirement that ticketing for the Park Service property be separated from that for Preservation Virginia property, we now have a ticketing tent near the boundary between the two. The archaeologists put down their trowels and raised the tent and then built a platform and desk for the ticketing team. Adjacent to the tent, inside the repurposed burial structure used at the 1607 burial ground in the fall, excavations are underway to give visitors a glimpse of the archaeology that takes place on Preservation Virginia property. The excavations have proved to be quite fruitful so far. The edges of four possible burials have been found, not surprising given the unit’s proximity to the site of the Church. In fact, one of the questions the team is hoping to answer by excavating here is where exactly the boundary of the churchyard is. The Great Road should also pass close to here, if not in the square the team is currently in, then in an adjacent one to be explored next. Some postholes of unknown purpose have been found as well as a pit or the edge of a ditch. Several artifacts have also turned up. A delft drug jar, copper scrap, two projectile points, iron nails, and modern bottle glass have all been found. The plan is to continue excavating within the bounds of the repurposed burial structure and moving the structure as needed to continue the dig. The structure is essentially a greenhouse and keeps the archaeologists warm, enabling excavations during the winter months.

In the Vault, additional pieces of a Portuguese faience dish were found while searching through the artifact archives, having been excavated in years past. Collections Assistant Lauren Stephens discovered that these pieces mended to each other and while obviously belonging to the existing partial dish, this new section doesn’t quite mend…it looks as though a few tiny sherds are missing. Portuguese faience is a tin glazed earthenware made in that country and this dish is decorated in the style of Chinese porcelain, bearing Artemisia leaves, laced bows, and flowering plants.

Senior Curator Leah Stricker has been working on gathering Jamestown’s collection of spoons together for the reference collection. We have four complete spoons (one of which was just found in the Governor’s Well) and dozens of fragmentary examples, being either the bowl, handle, terminal or a combination of the three. Pewter is the most common material type of spoons found at Jamestown, but unfortunately the acidic soil on the site causes significant degradation during the centuries they were underground. For these fragile finds, Jamestown conservators stabilize the items to prevent further decay, and take many images, including xrays, to capture the artifact as close to its time of excavation as possible.

Spoons and spoon elements made from copper alloy and lead survive in much more complete forms. Several of the spoon bowls have maker’s marks, and they tend to all be in the same place, near where the bowl meets the handle. One such maker’s mark bears a Tudor rose, while most are indiscernible. Some of the spoons have decorative terminals at the opposite side of the handle from the bowl. Among the terminals are examples shaped as acorns, the head of a maiden, and a seal that would be impressed into wax.

Senior Conservator Merry Outlaw is authoring a book on Chinese porcelain at Jamestown and the curatorial staff has been busy helping her gather and take measurements of the various vessels that will be included. One of the vessel types featured in the book are wine cups, with the examples in the collection having a remarkably standard shape and size. Another highlight of the collection is a tea bowl, a vessel form that typically doesn’t appear in English Virginia until the 1690s due to the fact that the English don’t start drinking tea until the mid-17th century. However, sherds from this tea bowl have been recovered from a feature that dates between 1610-1612 and two additional sherds were found this fall during the excavations at the 1607 burial ground.

Isotope samples from the colonists excavated at the 1607 burial ground this fall have been sent to the University of Georgia for processing and analysis. According to Associate Curator Emma Derry, the primary stable isotopes and metals that the team is interested in are carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, strontium, and lead. Stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen are used to determine what the colonists were eating. Stable oxygen isotopes can tell us about the origin of the water that they were drinking. The heavier oxygen 18 isotope — with 10 neutrons per atom instead of the usual 8 — is concentrated in the ocean, and colonists’ 18O values can be compared to isotopic maps of groundwater samples from different regions. Similarly, the bedrock in different locations has different ratios of the four strontium isotopes, and these are deposited in the body through drinking water and diet and can give clues to the origin of the plants and animals someone ate. Lead also has several isotopes that can be used to trace the origin of the material, but the overall concentration of lead in a person’s bones is also an important clue to social class in the 17th century. Lead was an important ingredient in high status objects including glazed earthenware dishes and pewter objects, so wealthier individuals tend to have higher concentrations of lead in their skeletons.

The conservation team was busy this month doing pXRF testing on some of the artifacts in the Archaearium museum. The technology was employed in the hopes of definitively ascertaining the chemical makeup of these artifacts. Knowing this enables the team to apply the appropriate conservation methods, stabilizing them so that visitors and researchers can have access to them for years to come. Among the objects subjected to this non-destructive testing were a pewter measure and flagon excavated from the Smithfield Well in 2002, a jet crucifix, and the Strachey ring. The pewter measure was confirmed as pewter but the flagon was more of a tinned copper alloy. Dr. Chris Wilkins, Senior Conservator, analyzed the results and remarked that some of the classifications are subjective and the ratios of the different metals comprising pewter would vary from maker to maker. pXRF samples were taken on both sides of the jet crucifix. On the front, the spot chosen for the testing was inside the depiction of Christ on the cross, starkly white against the jet black surrounding it. Lead was the big metal here, completely absent from the results on the rear side, so some sort of lead-based mixture was used for the color. pXRF testing was also performed on the Strachey ring, thought to belong to William Strachey, secretary of the colony. The results show that it’s made of a copper alloy.

dig deeper

related images

- The archaeological team installs a door for the ticketing tent.

- Director of Archaeology David Givens and Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown build the ticketing desk.

- The archaeological team uses linseed oil to finish the ticketing desk.

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber and Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown prepare the repurposed burial structure for excavations adjacent to the ticketing tent.

- A 2019 photo of graves discovered just east of the church wall. This pattern is similar to what the archaeologists have found along the western bounds of the excavations adjacent to the ticketing tent.

- The first archaeological square opened adjacent to the ticketing tent. A delft drug jar can be seen in the top left corner inside a pit or ditch and the edges of four probable burials can be seen along the right side.

- A partial delft drug jar found in the excavations adjacent to the ticketing tent

- A selection of artifacts found in the excavation square adjacent to the ticketing tent

- A quartz projectile point found during the excavations adjacent to the ticketing tent

- The newly-mended section of the Portuguese faience dish

- A Chinese porcelain wine cup in the Jamestown collection

- The Jamestown spoon collection

- The ridge running along the center of this brown object is a spoon handle which is degraded to the point that further corrosion removal efforts might damage what’s left of the original metal. Moving forward the plan is to stabilize the object to prevent further corrosion.

- A lead spoon bowl. Note the scratch marks inside the bowl.

- Senior Curator Leah Stricker points to an unidentified maker’s mark in the bowl of a fragmented spoon.

- Some of the spoon terminals in the Jamestown collection

- A spoon terminal in the form of a maiden’s head

- Senior Conservator Dr. Chris Wilkins reviews pXRF results from the flagon found in the Smithfield Well.

- pXRF results from the flagon found in the Smithfield Well showing the prevalence of elements in the sampling area.

- The pXRF results from the Strachey Ring showing the prevalence of elements in the sampling area.

- 2023 Field School student Eleanor Robb visited the staff in December and shared her painting of the 1608 fort extension construction. Pictured are Senior Staff Archaeologists Sean Romo and Mary Anna Hartley, Eleanor Robb, and Director of Archaeology David Givens

- 2023 field school student Eleanor Robb painted an illustration of the colonists working on the 1608 fort extension that she helped excavate.