Colonial Williamsburg helps translate the language of bricks

March XX, 2024. Natalie Reid, Staff Archaeologist

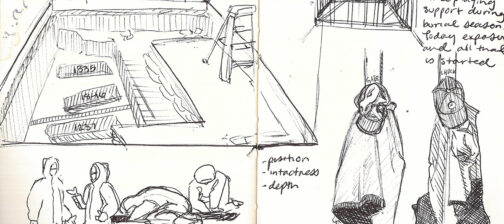

In October of 2023, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists completed the excavation of an early 17th-century well located just north of James Fort. The team believes the well dates to ca. 1617 and was constructed for Deputy Governor Samuel Argall. Notably, the well matched another well located 200 feet to the south: both were brick-lined and the circular structure on both was constructed using whole bricks separated by small, hand-made triangular brick wedges. In total, eight of the 24 courses of brick had to be removed in order for archaeologists to be able to reach the bottom of the well. Many of these removed bricks displayed intriguing marks and deformities that we wanted to investigate more thoroughly. Luckily, Colonial Williamsburg’s experts in Historic Trades were only a few minutes away. In February, CW Masonry Trades Manager Josh Graml, Journeyman of Masonry Trades Kenneth Tappan, and Brickmaker’s Apprentice Madeleine Bolton visited Jamestown to examine bricks from the Governor’s Well.

Having made thousands of bricks just like the 400-year old examples in front of them, Josh, Kenneth, and Madeleine were able to reverse-engineer how the bricks had been altered, damaged, or deformed. Their lived experience gave them unique insight into the life of a brick before it enters the kiln, and how the specific timeline of molding, drying, and firing creates a chronology of markings on the brick itself. Here are a few examples:

There are striking differences in the surfaces of these two bricks. One is smoother (on the right) while the other is much rougher (on the left). The smooth face of the brick on the right indicates that it was laid on dry ground to dry. The rough face on the other brick indicates that it was laid on wet ground to dry.

Parallel lines appear on many of the bricks. The CW team theorized a potential cause: when transporting bricks to begin the pre-kiln drying phase, a still-malleable brick gets stacked on a brickmaker’s wheelbarrow called a hackbarrow. The brickmakers theorized that the lines on the bricks may have been made by the slats that make up the bottom of the hackbarrow.

Chopping whole bricks into triangular wedges to create a rounded structure such as a well or arch is a task often given to novice brickmakers, both 400 years ago and today. Josh, Kenneth, and Madeleine laughed while reminiscing on their own experiences doing just this!

While talking about their early careers in brickmaking, the brickmakers were also drawn to bricks from the Governor’s Well where perhaps a less experienced or hurried brickmaker flung the too-wet clay out of its mold, causing it to warp. The high number of warped bricks could potentially mean that the brickmakers were rushed for some reason or another.

Though it may seem like a small detail, the motivations of the brickmakers and how quickly they had to build the well could speak volumes about the priorities set by the colony’s leaders. For a structure like the Governor’s Well, constructed ca. 1617, these details become hugely important when considering how little was recorded about Jamestown during the 1610s.

Ultimately, these new insights provide tremendous aid in the continuing research of the Governor’s Well. Though the excavation of the well is finished, the analysis of the artifacts—including each and every brick—has only just begun. In learning more about the well’s bricks, Jamestown Rediscovery staff are able to piece together the story of the well, including hints of the political climate of the colony during its construction. Additionally, working with colleagues from Colonial Williamsburg enables the team to not only compare the well with other brick structures on the island, but also with brick structures across the entire Historic Triangle area and beyond.

Stay tuned as we continue to learn more about the incredible artifacts excavated from the Governor’s Well.