As the weather grows colder the majority of the archaeological team has transitioned indoors, writing reports on recent field work and helping collections staff with artifact work in the lab. One or two archaeologists will continue work just south of the Archaearium or at the Godspeed Cottage as the weather permits. The colder temperatures also affect the ground itself. When the temperature descends below the freezing point, the moisture in the soil turns to ice, making it harder and more resistant to the effects of shovels and trowels. Freezing can also damage archaeological features and artifacts, so low temperatures mean the excavations must stay closed to protect the finds.

This month at the Archaearium dig, another possible brick-lined burial has been discovered, making it two found here. Past research suggests that the English didn’t line their graves with bricks until the 1650s. The team will continue to investigate this type of burial to pin down when the graves may date to. A large number of mammal bones, of both small and large species were found here this month, possibly indicating the presence of a midden. In the westernmost unit sits a large quantity of brick and plaster rubble, possibly related to deconstruction or repair of a structure after one of the fires that damaged the buildings on this ridge. Several sherds of a burned redware ceramic vessel were found close to the rubble. A wine bottle neck was found in these excavations this month as was another fragment of an exploded grenade, perhaps evidence of the events of September 19, 1676 when Nathaniel Bacon’s rebels captured and burned Jamestown. These bones, artifacts, and rubble are all coming from below the plowzone, meaning they represent original deposits. Although plowscars cut through the rubble, the material is largely intact.

Inside the Rediscovery Center, Senior Staff Archaeologist Dr. Chuck Durfor and Site Supervisor Anna Shackelford are working on a 3D model of the Memorial Church and 1680s Church Tower. The model will be used as a guide to help place new drainage for the Church and also as an asset for our virtual Jamestown efforts led by Staff Archaeologist Gabriel Brown. Chuck and Anna are using both digital SLR and drone photography to cover every angle of the structure. The photos are then placed on a 3D model of the Church as a type of skin, with the result being nearly photo-realistic. The software placing the skin on the model uses points placed by Chuck and Anna that define which parts of the photos match up with which parts of the model. Chuck handled the digital SLR photography, taking shots of everything except the roof, which is where Anna’s skill with the drone came in. Chuck is now merging all of the photos (2144 shots with the SLR camera, 440 with the drone) to create the model.

In the lab, the conservation staff is excited about the arrival of five new microscopes. The existing ones were lacking in areas such as lighting, magnification, and digital photography. Four of the new microscopes have a magnification range of 7x-100x whereas the old ones’ range was 10x-45x. They are trinocular microscopes, allowing for both eyes and a camera to view the object at once. The built-in camera takes 18 megapixel photos and an SLR camera can also be attached when especially high quality photos are desired. A fifth microscope, a light-polarizing type, has a magnification range of 50x-2500x and will allow for viewing of individual fibers of cordage such as the rope excavated from the Governor’s Well. This will enable identification of these fibers and artifacts such as wooden objects where viewing the cell structures is of primary importance in identifying the tree species from which they were made.

Jamestown Settlement, the living history museum just across the causeway from Historic Jamestowne, has generously provided our curatorial team a deceased iguana for comparative purposes. The lizard was cooked as part of 2024’s “Foods & Feasts of Colonial Virginia” event. Iguanas are not native to Virginia, but the settlers mention eating them while in the Caribbean, stopping there while following the trade winds on their way to Virginia. Earlier this year the first iguana bones were found in the collection, discovered while picking through faunal remains excavated from the “John Smith Well,” the fort’s first. Currently the iguana is in a freezer, but eventually it will be partially butchered, buried artificially in a plastic tote, and then it will decompose naturally until just the bones remain. The addition of a full iguana skeleton to our comparative collection will make identifying any future iguana remains much easier.

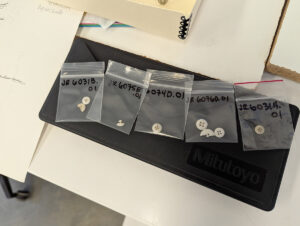

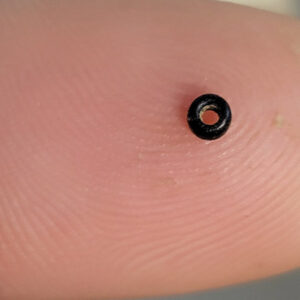

Associate Curator Janene Johnston has added representative examples of prosser buttons to the reference collection. These ceramic buttons have a sew-through design and were invented around 1840. They speak to the centuries of human occupation of Jamestown Island after it ceased to be Virginia’s capital in 1699, as farmland and historic attraction. Assistant Curator Magen Hodapp has completed her processing of layer “W” of the John Smith well. The hundreds of thousands of bones will now go to outside zooarchaeologists Steve Atkins and Susan Andrews who will look for details such as butchery patterns, signs of burning, age, and sex. They will also further categorize the bones by species where possible. Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber, in the lab to help the curatorial staff during the winter months, found a tiny glass bead while picking through the heavy fraction of floated soil excavated from Pit 1, one of the first features discovered by Jamestown Rediscovery in 1994.

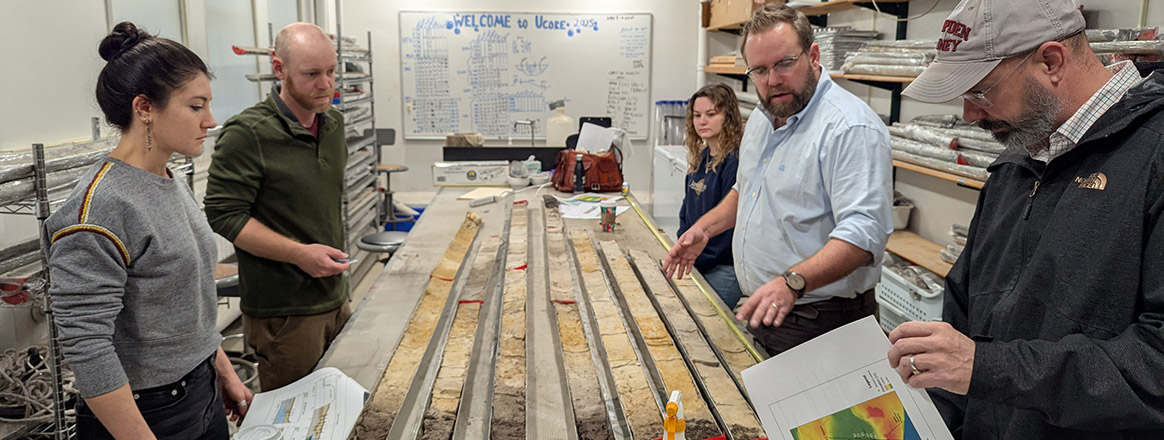

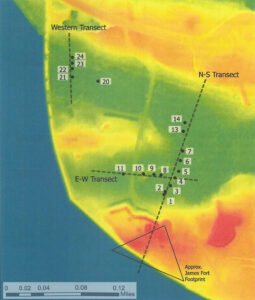

Director of Archaeology Sean Romo, Director of Conservation and Collections Michael Lavin, and Associate Curator Emma Derry traveled to New England this month to meet with partners in the fields of ancient DNA and geology. The first stop was the University of Connecticut where the trio met with professors Drs. Dave Leslie and Will Ouimet, and undergrad Cassie Aimetti to discuss the findings of the vibracore samples taken at Jamestown in June. Vibracoring uses vibration to force a hollow metal tube into the ground, taking a sample of soil ten feet deep or more that is extracted using a jack and then opened and analyzed in a lab. Of special importance to the team are two goals: identifying sections of the Great Road, and determining which sections of the Pitch and Tar Swamp are 20th and 21st century phenomena (relatively new occurrences).

Referring to the map at (right), cores 13, 14, 23, and 24 have no plowzone layer, meaning they were either never farmed or the plowzone has since been disturbed. Cores 20, 23, and 24 have a sandy layer that may be evidence of the Great Road. Core 7 has a plowzone layer underneath a marsh layer, indicating that the area was previously farmed (and dry enough to do so). The swamp there is a relatively new phenomenon, which jibes with what long-time employees of Jamestown Rediscovery remember…land that was once a field is now underwater. Core 13 contained a large charcoal deposit, evidence of a forest fire that occurred over 35,000 years ago according to Dr. Leslie. Several of the core samples analyzed using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) showed a spike in lead that could be related to manufacturing processes (metallurgy, glass making) undertaken by the colonists. But it could also be natural. Further vibracore samples might help settle this question by looking for patterns of increased and decreased lead levels at various distances from industrial areas discovered archaeologically.

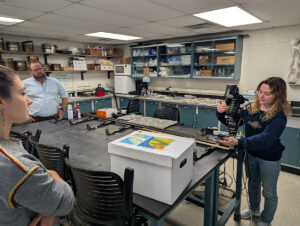

Ms. Aimetti demonstrated a macropod scanner that she uses to photograph each of the cores. A digital SLR camera is a component of the scanner, which is moved along a track at measured increments down the length of the core, with photographs taken at each increment. Post processing that includes both software and human analyzation results in a single digital image stitched together from the multiple photographs. There is a yardstick that runs parallel to the core that helps Ms. Aimetti combine sections of the core that are devoid of the distinguishing features that help both computers and humans determine where the photographs overlap. When she’s done, there is a high-resolution photograph record of each core that can be zoomed and panned without needing access to the core itself.

X-ray fluorescence scans of the cores are also taken, at set intervals along the length of the core. This process involves a pXRF (portable X-ray fluorescence) device that bombards a material with x-rays. The material emits x-rays back at the device, with different materials (the atoms comprising them) responding with characteristic wavelengths that are used to identify them. The UConn team uses specified intervals for pXRF scans (every 2 cm in this case) to get an aggregate of the data, so that a single scan isn’t definitive for a length of the core. The data obtained using pXRF along the length of the core shows elemental composition through time, and so changes — for instance an increase in the presence of lead — may be an indicator of the arrival of the colonists and give clues about the industries they were involved in.

The team next had a discussion with UConn’s Dr. Deborah Bolnick, professor, anthropological geneticist, and director of UConn’s Anthropological Genomics Lab. Dr. Bolnick is a partner in the bioarchaeology project at Jamestown, overseeing the extraction and analysis of colonists’ DNA. Sean, Michael, and Emma discussed possible other means of extracting DNA, perhaps even when only stains in the soil remain, especially pertinent to our excavations in Smithfield, with its low-lying disposition leaving it prone to increasing flooding. This flooding is subjecting the settlers buried there to wet-dry cycles that dissolve the skeletal remains but leave stains in the soil. Could DNA be extracted from the stains themselves? We don’t know, but with Dr. Bolnick’s help we hope to find out. Experiments such as the successful extraction of DNA from a 19th-century pipe stem give us hope. If successful, this method could also open up avenues of research for DNA extraction when the traditional methods of obtaining DNA — necessarily partially destructive — are not an option.

Travelling next to Dartmouth College, Sean, Michael, and Emma had a discussion with Dr. Raquel Fleskes, professor and molecular anthropologist who has extracted and processed the DNA of many of the Jamestown colonists. Dr. Fleskes let the team know that no viable DNA could be recovered from JR1225B, the young man found in the 1607 burial ground with a projectile point next to his left femur. It is thought that he may have died during the May 26, 1607 attack by Virginia Indians, prior to the construction of James Fort. The inability to recover viable DNA from 400-year-old skeletons is unfortunate but common. The field is rapidly changing, with current methodologies yielding results that were impossible 20 years ago. Hopefully future technology and methods will yield results where current means fall short. Next the group discussed a rough five year master plan for continued burial DNA analysis, determining how many burials are feasible each year, and considering possible collaborations on NSF (National Science Foundation) grants to support future work. The group agreed that community engagement with descendant communities must remain an important part of the process.

related images

- Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber, Staff Archaeologist Natalie Reid, and Director of Archaeology Sean Romo discuss the brick and rubble pile at the Archaearium excavation site.

- Mammal bones are interspersed with brick rubble as found by archaeologists in the excavations south of the Archaearium.

- Archaeological Field Technicians Eleanor Robb and Hannah Barch and Staff Archaeologist Caitlin Delmas screen soil excavated from the dig south of the Archaearium.

- A burned ceramic sherd found in the excavations south of the Archaearium

- Burned redware ceramic sherds found in the excavations south of the Archaearium

- A wine bottle neck found in the excavations south of the Archaearium

- Another view of the wine bottle neck found south of the Archaearium

- A fragment of an exploded grenade found in the excavations just south of the Archaearium

- Associate Curator Emma Derry and Dr. Deborah Bolnick unpack bone samples for DNA processing.

- Director of Archaeology Sean Romo and University of Connecticut’s Dr. David Leslie inspect a large section of charcoal in one of the Jamestown vibracore samples — evidence of a forest fire that occurred more than 35,000 years ago.

- Some of the latest vibracore samples from Jamestown in the UConn lab

- Jamestown vibracore samples

- Associate Curator Emma Derry, Director of Archaeology Sean Romo, University of Connecticut’s Cassie Aimetti and Dr. David Leslie, and Director of Collections and Conservation Michael Lavin examine the latest batch of vibracore samples from Jamestown.

- A tiny glass bead found by Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber while sorting through objects from Pit 1.

- Another shot of the glass bead found by Archaeological Field Technician Josh Barber while sorting through objects found in Pit 1.

- Dr. Chris Wilkins demonstrates use of the new light polarizing microscope.